Welcome to the world of state area fashions. On this world, there’s a latent course of, hidden from our eyes; and there are observations we make concerning the issues it produces. The method evolves on account of some hidden logic (transition mannequin); and the way in which it produces the observations follows some hidden logic (remark mannequin). There’s noise in course of evolution, and there’s noise in remark. If the transition and remark fashions each are linear, and the method in addition to remark noise are Gaussian, we have now a linear-Gaussian state area mannequin (SSM). The duty is to deduce the latent state from the observations. Essentially the most well-known approach is the Kálmán filter.

In sensible functions, two traits of linear-Gaussian SSMs are particularly engaging.

For one, they allow us to estimate dynamically altering parameters. In regression, the parameters could be seen as a hidden state; we could thus have a slope and an intercept that change over time. When parameters can range, we communicate of dynamic linear fashions (DLMs). That is the time period we’ll use all through this put up when referring to this class of fashions.

Second, linear-Gaussian SSMs are helpful in time-series forecasting as a result of Gaussian processes could be added. A time collection can thus be framed as, e.g. the sum of a linear pattern and a course of that varies seasonally.

Utilizing tfprobability, the R wrapper to TensorFlow Likelihood, we illustrate each elements right here. Our first instance will likely be on dynamic linear regression. In an in depth walkthrough, we present on the right way to match such a mannequin, the right way to receive filtered, in addition to smoothed, estimates of the coefficients, and the right way to receive forecasts.

Our second instance then illustrates course of additivity. This instance will construct on the primary, and may function a fast recap of the general process.

Let’s bounce in.

Dynamic linear regression instance: Capital Asset Pricing Mannequin (CAPM)

Our code builds on the just lately launched variations of TensorFlow and TensorFlow Likelihood: 1.14 and 0.7, respectively.

Be aware how there’s one factor we used to do currently that we’re not doing right here: We’re not enabling keen execution. We are saying why in a minute.

Our instance is taken from Petris et al.(2009)(Petris, Petrone, and Campagnoli 2009), chapter 3.2.7.

Apart from introducing the dlm package deal, this guide offers a pleasant introduction to the concepts behind DLMs typically.

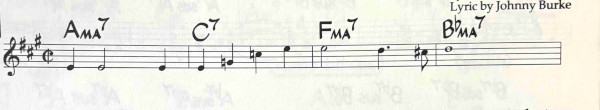

As an example dynamic linear regression, the authors characteristic a dataset, initially from Berndt(1991)(Berndt 1991) that has month-to-month returns, collected from January 1978 to December 1987, for 4 totally different shares, the 30-day Treasury Invoice – standing in for a risk-free asset –, and the value-weighted common returns for all shares listed on the New York and American Inventory Exchanges, representing the general market returns.

Let’s have a look.

# As the information doesn't appear to be out there on the tackle given in Petris et al. any extra,

# we put it on the weblog for obtain

# obtain from:

# https://github.com/rstudio/tensorflow-blog/blob/grasp/docs/posts/2019-06-25-dynamic_linear_models_tfprobability/knowledge/capm.txt"

df <- read_table(

"capm.txt",

col_types = record(X1 = col_date(format = "%Y.%m"))) %>%

rename(month = X1)

df %>% glimpse()

Observations: 120

Variables: 7

$ month 1978-01-01, 1978-02-01, 1978-03-01, 1978-04-01, 1978-05-01, 19…

$ MOBIL -0.046, -0.017, 0.049, 0.077, -0.011, -0.043, 0.028, 0.056, 0.0…

$ IBM -0.029, -0.043, -0.063, 0.130, -0.018, -0.004, 0.092, 0.049, -0…

$ WEYER -0.116, -0.135, 0.084, 0.144, -0.031, 0.005, 0.164, 0.039, -0.0…

$ CITCRP -0.115, -0.019, 0.059, 0.127, 0.005, 0.007, 0.032, 0.088, 0.011…

$ MARKET -0.045, 0.010, 0.050, 0.063, 0.067, 0.007, 0.071, 0.079, 0.002,…

$ RKFREE 0.00487, 0.00494, 0.00526, 0.00491, 0.00513, 0.00527, 0.00528, …

df %>% collect(key = "image", worth = "return", -month) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = month, y = return, coloration = image)) +

geom_line() +

facet_grid(rows = vars(image), scales = "free")

The Capital Asset Pricing Mannequin then assumes a linear relationship between the surplus returns of an asset beneath examine and the surplus returns of the market. For each, extra returns are obtained by subtracting the returns of the chosen risk-free asset; then, the scaling coefficient between them reveals the asset to both be an “aggressive” funding (slope > 1: modifications out there are amplified), or a conservative one (slope < 1: modifications are damped).

Assuming this relationship doesn’t change over time, we will simply use lm as an example this. Following Petris et al. in zooming in on IBM because the asset beneath examine, we have now

# extra returns of the asset beneath examine

ibm <- df$IBM - df$RKFREE

# market extra returns

x <- df$MARKET - df$RKFREE

match <- lm(ibm ~ x)

abstract(match)

Name:

lm(method = ibm ~ x)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.11850 -0.03327 -0.00263 0.03332 0.15042

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t worth Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -0.0004896 0.0046400 -0.106 0.916

x 0.4568208 0.0675477 6.763 5.49e-10 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual normal error: 0.05055 on 118 levels of freedom

A number of R-squared: 0.2793, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2732

F-statistic: 45.74 on 1 and 118 DF, p-value: 5.489e-10

So IBM is discovered to be a conservative funding, the slope being ~ 0.5. However is that this relationship steady over time?

Let’s flip to tfprobability to research.

We need to use this instance to reveal two important functions of DLMs: acquiring smoothing and/or filtering estimates of the coefficients, in addition to forecasting future values. So not like Petris et al., we divide the dataset right into a coaching and a testing half:.

# zoom in on ibm

ts <- ibm %>% matrix()

# forecast 12 months

n_forecast_steps <- 12

ts_train <- ts[1:(length(ts) - n_forecast_steps), 1, drop = FALSE]

# be certain that we work with float32 right here

ts_train <- tf$solid(ts_train, tf$float32)

ts <- tf$solid(ts, tf$float32)

We now assemble the mannequin. sts_dynamic_linear_regression() does what we would like:

# outline the mannequin on the entire collection

linreg <- ts %>%

sts_dynamic_linear_regression(

design_matrix = cbind(rep(1, size(x)), x) %>% tf$solid(tf$float32)

)

We cross it the column of extra market returns, plus a column of ones, following Petris et al.. Alternatively, we may heart the one predictor – this may work simply as effectively.

How are we going to coach this mannequin? Technique-wise, we have now a alternative between variational inference (VI) and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC). We’ll see each. The second query is: Are we going to make use of graph mode or keen mode? As of at the moment, for each VI and HMC, it’s most secure – and quickest – to run in graph mode, so that is the one approach we present. In a number of weeks, or months, we should always be capable to prune loads of sess$run()s from the code!

Usually in posts, when presenting code we optimize for simple experimentation (that means: line-by-line executability), not modularity. This time although, with an vital variety of analysis statements concerned, it’s best to pack not simply the becoming, however the smoothing and forecasting as effectively right into a perform (which you may nonetheless step by means of should you wished). For VI, we’ll have a match _with_vi perform that does all of it. So once we now begin explaining what it does, don’t sort within the code simply but – it’ll all reappear properly packed into that perform, so that you can copy and execute as a complete.

Becoming a time collection with variational inference

Becoming with VI just about seems like coaching historically used to look in graph-mode TensorFlow. You outline a loss – right here it’s finished utilizing sts_build_factored_variational_loss() –, an optimizer, and an operation for the optimizer to cut back that loss:

optimizer <- tf$compat$v1$prepare$AdamOptimizer(0.1)

# solely prepare on the coaching set!

loss_and_dists <- ts_train %>% sts_build_factored_variational_loss(mannequin = mannequin)

variational_loss <- loss_and_dists[[1]]

train_op <- optimizer$reduce(variational_loss)

Be aware how the loss is outlined on the coaching set solely, not the entire collection.

Now to truly prepare the mannequin, we create a session and run that operation:

with (tf$Session() %as% sess, {

sess$run(tf$compat$v1$global_variables_initializer())

for (step in 1:n_iterations) {

res <- sess$run(train_op)

loss <- sess$run(variational_loss)

if (step %% 10 == 0)

cat("Loss: ", as.numeric(loss), "n")

}

})

Given we have now that session, let’s make use of it and compute all of the estimates we want.

Once more, – the next snippets will find yourself within the fit_with_vi perform, so don’t run them in isolation simply but.

Acquiring forecasts

The very first thing we would like for the mannequin to provide us are forecasts. In an effort to create them, it wants samples from the posterior. Fortunately we have already got the posterior distributions, returned from sts_build_factored_variational_loss, so let’s pattern from them and cross them to sts_forecast:

variational_distributions <- loss_and_dists[[2]]

posterior_samples <-

Map(

perform(d) d %>% tfd_sample(n_param_samples),

variational_distributions %>% reticulate::py_to_r() %>% unname()

)

forecast_dists <- ts_train %>% sts_forecast(mannequin, posterior_samples, n_forecast_steps)

sts_forecast() returns distributions, so we name tfd_mean() to get the posterior predictions and tfd_stddev() for the corresponding normal deviations:

fc_means <- forecast_dists %>% tfd_mean()

fc_sds <- forecast_dists %>% tfd_stddev()

By the way in which – as we have now the total posterior distributions, we’re on no account restricted to abstract statistics! We may simply use tfd_sample() to acquire particular person forecasts.

Smoothing and filtering (Kálmán filter)

Now, the second (and final, for this instance) factor we are going to need are the smoothed and filtered regression coefficients. The well-known Kálmán Filter is a Bayesian-in-spirit technique the place at every time step, predictions are corrected by how a lot they differ from an incoming remark. Filtering estimates are based mostly on observations we’ve seen up to now; smoothing estimates are computed “in hindsight,” making use of the entire time collection.

We first create a state area mannequin from our time collection definition:

# solely do that on the coaching set

# returns an occasion of tfd_linear_gaussian_state_space_model()

ssm <- mannequin$make_state_space_model(size(ts_train), param_vals = posterior_samples)

tfd_linear_gaussian_state_space_model(), technically a distribution, offers the Kálmán filter functionalities of smoothing and filtering.

To acquire the smoothed estimates:

c(smoothed_means, smoothed_covs) %<-% ssm$posterior_marginals(ts_train)

And the filtered ones:

c(., filtered_means, filtered_covs, ., ., ., .) %<-% ssm$forward_filter(ts_train)

Lastly, we have to consider all these.

c(posterior_samples, fc_means, fc_sds, smoothed_means, smoothed_covs, filtered_means, filtered_covs) %<-%

sess$run(record(posterior_samples, fc_means, fc_sds, smoothed_means, smoothed_covs, filtered_means, filtered_covs))

Placing all of it collectively (the VI version)

So right here’s the entire perform, fit_with_vi, prepared for us to name.

fit_with_vi <-

perform(ts,

ts_train,

mannequin,

n_iterations,

n_param_samples,

n_forecast_steps,

n_forecast_samples) {

optimizer <- tf$compat$v1$prepare$AdamOptimizer(0.1)

loss_and_dists <-

ts_train %>% sts_build_factored_variational_loss(mannequin = mannequin)

variational_loss <- loss_and_dists[[1]]

train_op <- optimizer$reduce(variational_loss)

with (tf$Session() %as% sess, {

sess$run(tf$compat$v1$global_variables_initializer())

for (step in 1:n_iterations) {

sess$run(train_op)

loss <- sess$run(variational_loss)

if (step %% 1 == 0)

cat("Loss: ", as.numeric(loss), "n")

}

variational_distributions <- loss_and_dists[[2]]

posterior_samples <-

Map(

perform(d)

d %>% tfd_sample(n_param_samples),

variational_distributions %>% reticulate::py_to_r() %>% unname()

)

forecast_dists <-

ts_train %>% sts_forecast(mannequin, posterior_samples, n_forecast_steps)

fc_means <- forecast_dists %>% tfd_mean()

fc_sds <- forecast_dists %>% tfd_stddev()

ssm <- mannequin$make_state_space_model(size(ts_train), param_vals = posterior_samples)

c(smoothed_means, smoothed_covs) %<-% ssm$posterior_marginals(ts_train)

c(., filtered_means, filtered_covs, ., ., ., .) %<-% ssm$forward_filter(ts_train)

c(posterior_samples, fc_means, fc_sds, smoothed_means, smoothed_covs, filtered_means, filtered_covs) %<-%

sess$run(record(posterior_samples, fc_means, fc_sds, smoothed_means, smoothed_covs, filtered_means, filtered_covs))

})

record(

variational_distributions,

posterior_samples,

fc_means[, 1],

fc_sds[, 1],

smoothed_means,

smoothed_covs,

filtered_means,

filtered_covs

)

}

And that is how we name it.

# variety of VI steps

n_iterations <- 300

# pattern measurement for posterior samples

n_param_samples <- 50

# pattern measurement to attract from the forecast distribution

n_forecast_samples <- 50

# here is the mannequin once more

mannequin <- ts %>%

sts_dynamic_linear_regression(design_matrix = cbind(rep(1, size(x)), x) %>% tf$solid(tf$float32))

# name fit_vi outlined above

c(

param_distributions,

param_samples,

fc_means,

fc_sds,

smoothed_means,

smoothed_covs,

filtered_means,

filtered_covs

) %<-% fit_vi(

ts,

ts_train,

mannequin,

n_iterations,

n_param_samples,

n_forecast_steps,

n_forecast_samples

)

Curious concerning the outcomes? We’ll see them in a second, however earlier than let’s simply rapidly look on the different coaching technique: HMC.

Placing all of it collectively (the HMC version)

tfprobability offers sts_fit_with_hmc to suit a DLM utilizing Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. Latest posts (e.g., Hierarchical partial pooling, continued: Various slopes fashions with TensorFlow Likelihood) confirmed the right way to arrange HMC to suit hierarchical fashions; right here a single perform does all of it.

Right here is fit_with_hmc, wrapping sts_fit_with_hmc in addition to the (unchanged) strategies for acquiring forecasts and smoothed/filtered parameters:

num_results <- 200

num_warmup_steps <- 100

fit_hmc <- perform(ts,

ts_train,

mannequin,

num_results,

num_warmup_steps,

n_forecast,

n_forecast_samples) {

states_and_results <-

ts_train %>% sts_fit_with_hmc(

mannequin,

num_results = num_results,

num_warmup_steps = num_warmup_steps,

num_variational_steps = num_results + num_warmup_steps

)

posterior_samples <- states_and_results[[1]]

forecast_dists <-

ts_train %>% sts_forecast(mannequin, posterior_samples, n_forecast_steps)

fc_means <- forecast_dists %>% tfd_mean()

fc_sds <- forecast_dists %>% tfd_stddev()

ssm <-

mannequin$make_state_space_model(size(ts_train), param_vals = posterior_samples)

c(smoothed_means, smoothed_covs) %<-% ssm$posterior_marginals(ts_train)

c(., filtered_means, filtered_covs, ., ., ., .) %<-% ssm$forward_filter(ts_train)

with (tf$Session() %as% sess, {

sess$run(tf$compat$v1$global_variables_initializer())

c(

posterior_samples,

fc_means,

fc_sds,

smoothed_means,

smoothed_covs,

filtered_means,

filtered_covs

) %<-%

sess$run(

record(

posterior_samples,

fc_means,

fc_sds,

smoothed_means,

smoothed_covs,

filtered_means,

filtered_covs

)

)

})

record(

posterior_samples,

fc_means[, 1],

fc_sds[, 1],

smoothed_means,

smoothed_covs,

filtered_means,

filtered_covs

)

}

c(

param_samples,

fc_means,

fc_sds,

smoothed_means,

smoothed_covs,

filtered_means,

filtered_covs

) %<-% fit_hmc(ts,

ts_train,

mannequin,

num_results,

num_warmup_steps,

n_forecast,

n_forecast_samples)

Now lastly, let’s check out the forecasts and filtering resp. smoothing estimates.

Forecasts

Placing all we want into one dataframe, we have now

smoothed_means_intercept <- smoothed_means[, , 1] %>% colMeans()

smoothed_means_slope <- smoothed_means[, , 2] %>% colMeans()

smoothed_sds_intercept <- smoothed_covs[, , 1, 1] %>% colMeans() %>% sqrt()

smoothed_sds_slope <- smoothed_covs[, , 2, 2] %>% colMeans() %>% sqrt()

filtered_means_intercept <- filtered_means[, , 1] %>% colMeans()

filtered_means_slope <- filtered_means[, , 2] %>% colMeans()

filtered_sds_intercept <- filtered_covs[, , 1, 1] %>% colMeans() %>% sqrt()

filtered_sds_slope <- filtered_covs[, , 2, 2] %>% colMeans() %>% sqrt()

forecast_df <- df %>%

choose(month, IBM) %>%

add_column(pred_mean = c(rep(NA, size(ts_train)), fc_means)) %>%

add_column(pred_sd = c(rep(NA, size(ts_train)), fc_sds)) %>%

add_column(smoothed_means_intercept = c(smoothed_means_intercept, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(smoothed_means_slope = c(smoothed_means_slope, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(smoothed_sds_intercept = c(smoothed_sds_intercept, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(smoothed_sds_slope = c(smoothed_sds_slope, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(filtered_means_intercept = c(filtered_means_intercept, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(filtered_means_slope = c(filtered_means_slope, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(filtered_sds_intercept = c(filtered_sds_intercept, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(filtered_sds_slope = c(filtered_sds_slope, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps)))

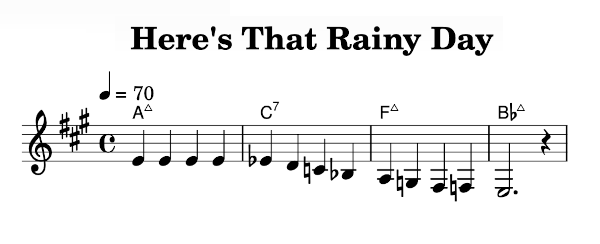

So right here first are the forecasts. We’re utilizing the estimates returned from VI, however we may simply as effectively have used these from HMC – they’re practically indistinguishable. The identical goes for the filtering and smoothing estimates displayed beneath.

ggplot(forecast_df, aes(x = month, y = IBM)) +

geom_line(coloration = "gray") +

geom_line(aes(y = pred_mean), coloration = "cyan") +

geom_ribbon(

aes(ymin = pred_mean - 2 * pred_sd, ymax = pred_mean + 2 * pred_sd),

alpha = 0.2,

fill = "cyan"

) +

theme(axis.title = element_blank())

Smoothing estimates

Listed below are the smoothing estimates. The intercept (proven in orange) stays fairly steady over time, however we do see a pattern within the slope (displayed in inexperienced).

ggplot(forecast_df, aes(x = month, y = smoothed_means_intercept)) +

geom_line(coloration = "orange") +

geom_line(aes(y = smoothed_means_slope),

coloration = "inexperienced") +

geom_ribbon(

aes(

ymin = smoothed_means_intercept - 2 * smoothed_sds_intercept,

ymax = smoothed_means_intercept + 2 * smoothed_sds_intercept

),

alpha = 0.3,

fill = "orange"

) +

geom_ribbon(

aes(

ymin = smoothed_means_slope - 2 * smoothed_sds_slope,

ymax = smoothed_means_slope + 2 * smoothed_sds_slope

),

alpha = 0.1,

fill = "inexperienced"

) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(forecast_df$month[1], forecast_df$month[length(ts) - n_forecast_steps])) +

theme(axis.title = element_blank())

Filtering estimates

For comparability, listed below are the filtering estimates. Be aware that the y-axis extends additional up and down, so we will seize uncertainty higher:

ggplot(forecast_df, aes(x = month, y = filtered_means_intercept)) +

geom_line(coloration = "orange") +

geom_line(aes(y = filtered_means_slope),

coloration = "inexperienced") +

geom_ribbon(

aes(

ymin = filtered_means_intercept - 2 * filtered_sds_intercept,

ymax = filtered_means_intercept + 2 * filtered_sds_intercept

),

alpha = 0.3,

fill = "orange"

) +

geom_ribbon(

aes(

ymin = filtered_means_slope - 2 * filtered_sds_slope,

ymax = filtered_means_slope + 2 * filtered_sds_slope

),

alpha = 0.1,

fill = "inexperienced"

) +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(-2, 2),

xlim = c(forecast_df$month[1], forecast_df$month[length(ts) - n_forecast_steps])) +

theme(axis.title = element_blank())

To date, we’ve seen a full instance of time-series becoming, forecasting, and smoothing/filtering, in an thrilling setting one doesn’t encounter too usually: dynamic linear regression. What we haven’t seen as but is the additivity characteristic of DLMs, and the way it permits us to decompose a time collection into its (theorized) constituents.

Let’s do that subsequent, in our second instance, anti-climactically making use of the iris of time collection, AirPassengers. Any guesses what parts the mannequin may presuppose?

Composition instance: AirPassengers

Libraries loaded, we put together the information for tfprobability:

The mannequin is a sum – cf. sts_sum – of a linear pattern and a seasonal element:

linear_trend <- ts %>% sts_local_linear_trend()

month-to-month <- ts %>% sts_seasonal(num_seasons = 12)

mannequin <- ts %>% sts_sum(parts = record(month-to-month, linear_trend))

Once more, we may use VI in addition to MCMC to coach the mannequin. Right here’s the VI method:

n_iterations <- 100

n_param_samples <- 50

n_forecast_samples <- 50

optimizer <- tf$compat$v1$prepare$AdamOptimizer(0.1)

fit_vi <-

perform(ts,

ts_train,

mannequin,

n_iterations,

n_param_samples,

n_forecast_steps,

n_forecast_samples) {

loss_and_dists <-

ts_train %>% sts_build_factored_variational_loss(mannequin = mannequin)

variational_loss <- loss_and_dists[[1]]

train_op <- optimizer$reduce(variational_loss)

with (tf$Session() %as% sess, {

sess$run(tf$compat$v1$global_variables_initializer())

for (step in 1:n_iterations) {

res <- sess$run(train_op)

loss <- sess$run(variational_loss)

if (step %% 1 == 0)

cat("Loss: ", as.numeric(loss), "n")

}

variational_distributions <- loss_and_dists[[2]]

posterior_samples <-

Map(

perform(d)

d %>% tfd_sample(n_param_samples),

variational_distributions %>% reticulate::py_to_r() %>% unname()

)

forecast_dists <-

ts_train %>% sts_forecast(mannequin, posterior_samples, n_forecast_steps)

fc_means <- forecast_dists %>% tfd_mean()

fc_sds <- forecast_dists %>% tfd_stddev()

c(posterior_samples,

fc_means,

fc_sds) %<-%

sess$run(record(posterior_samples,

fc_means,

fc_sds))

})

record(variational_distributions,

posterior_samples,

fc_means[, 1],

fc_sds[, 1])

}

c(param_distributions,

param_samples,

fc_means,

fc_sds) %<-% fit_vi(

ts,

ts_train,

mannequin,

n_iterations,

n_param_samples,

n_forecast_steps,

n_forecast_samples

)

For brevity, we haven’t computed smoothed and/or filtered estimates for the general mannequin. On this instance, this being a sum mannequin, we need to present one thing else as an alternative: the way in which it decomposes into parts.

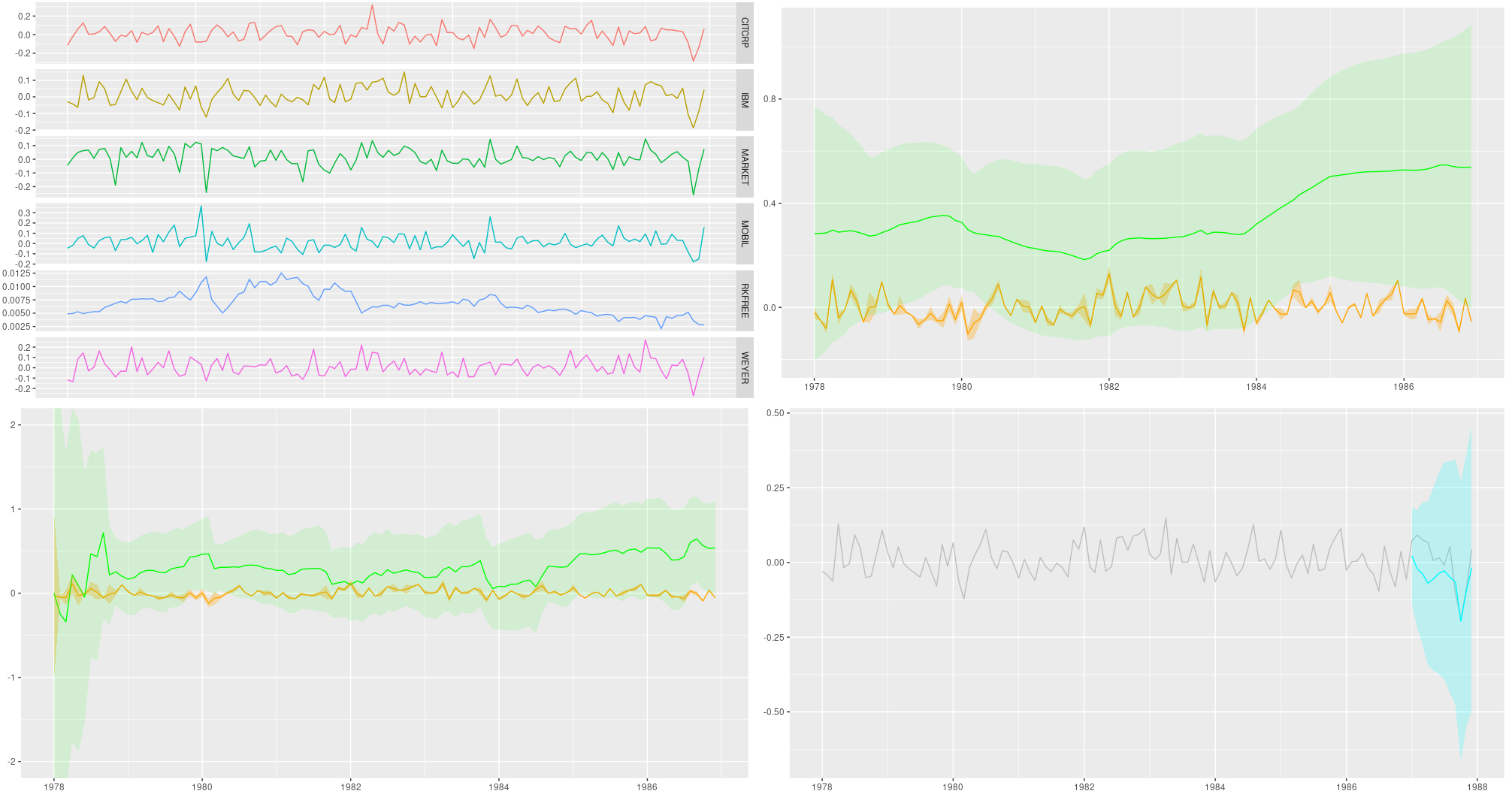

However first, the forecasts:

forecast_df <- df %>%

add_column(pred_mean = c(rep(NA, size(ts_train)), fc_means)) %>%

add_column(pred_sd = c(rep(NA, size(ts_train)), fc_sds))

ggplot(forecast_df, aes(x = month, y = n)) +

geom_line(coloration = "gray") +

geom_line(aes(y = pred_mean), coloration = "cyan") +

geom_ribbon(

aes(ymin = pred_mean - 2 * pred_sd, ymax = pred_mean + 2 * pred_sd),

alpha = 0.2,

fill = "cyan"

) +

theme(axis.title = element_blank())

A name to sts_decompose_by_component yields the (centered) parts, a linear pattern and a seasonal issue:

component_dists <-

ts_train %>% sts_decompose_by_component(mannequin = mannequin, parameter_samples = param_samples)

seasonal_effect_means <- component_dists[[1]] %>% tfd_mean()

seasonal_effect_sds <- component_dists[[1]] %>% tfd_stddev()

linear_effect_means <- component_dists[[2]] %>% tfd_mean()

linear_effect_sds <- component_dists[[2]] %>% tfd_stddev()

with(tf$Session() %as% sess, {

c(

seasonal_effect_means,

seasonal_effect_sds,

linear_effect_means,

linear_effect_sds

) %<-% sess$run(

record(

seasonal_effect_means,

seasonal_effect_sds,

linear_effect_means,

linear_effect_sds

)

)

})

components_df <- forecast_df %>%

add_column(seasonal_effect_means = c(seasonal_effect_means, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(seasonal_effect_sds = c(seasonal_effect_sds, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(linear_effect_means = c(linear_effect_means, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps))) %>%

add_column(linear_effect_sds = c(linear_effect_sds, rep(NA, n_forecast_steps)))

ggplot(components_df, aes(x = month, y = n)) +

geom_line(aes(y = seasonal_effect_means), coloration = "orange") +

geom_ribbon(

aes(

ymin = seasonal_effect_means - 2 * seasonal_effect_sds,

ymax = seasonal_effect_means + 2 * seasonal_effect_sds

),

alpha = 0.2,

fill = "orange"

) +

theme(axis.title = element_blank()) +

geom_line(aes(y = linear_effect_means), coloration = "inexperienced") +

geom_ribbon(

aes(

ymin = linear_effect_means - 2 * linear_effect_sds,

ymax = linear_effect_means + 2 * linear_effect_sds

),

alpha = 0.2,

fill = "inexperienced"

) +

theme(axis.title = element_blank())

Wrapping up

We’ve seen how with DLMs, there’s a bunch of attention-grabbing stuff you are able to do – other than acquiring forecasts, which in all probability would be the final objective in most functions – : You possibly can examine the smoothed and the filtered estimates from the Kálmán filter, and you’ll decompose a mannequin into its posterior parts. A very engaging mannequin is dynamic linear regression, featured in our first instance, which permits us to acquire regression coefficients that change over time.

This put up confirmed the right way to accomplish this with tfprobability. As of at the moment, TensorFlow (and thus, TensorFlow Likelihood) is in a state of considerable inside modifications, with wanting to turn into the default execution mode very quickly. Concurrently, the superior TensorFlow Likelihood improvement crew are including new and thrilling options day-after-day. Consequently, this put up is snapshot capturing the right way to greatest accomplish these targets now: For those who’re studying this a number of months from now, likelihood is that what’s work in progress now could have turn into a mature technique by then, and there could also be sooner methods to achieve the identical targets. On the price TFP is evolving, we’re excited for the issues to come back!

Berndt, R. 1991. The Observe of Econometrics. Addison-Wesley.

Murphy, Kevin. 2012. Machine Studying: A Probabilistic Perspective. MIT Press.

Petris, Giovanni, sonia Petrone, and Patrizia Campagnoli. 2009. Dynamic Linear Fashions with r. Springer.

Take pleasure in this weblog? Get notified of latest posts by electronic mail:

Posts additionally out there at r-bloggers