(newcommand{epsb}{{boldsymbol{epsilon}}}

newcommand{mub}{{boldsymbol{mu}}}

newcommand{thetab}{{boldsymbol{theta}}}

newcommand{Thetab}{{boldsymbol{Theta}}}

newcommand{etab}{{boldsymbol{eta}}}

newcommand{Sigmab}{{boldsymbol{Sigma}}}

newcommand{Phib}{{boldsymbol{Phi}}}

newcommand{Phat}{hat{{bf P}}})Vector autoregression (VAR) is a useful gizmo for analyzing the dynamics of a number of time sequence. VAR expresses a vector of noticed variables as a operate of its personal lags.

Simulation

Let’s start by simulating a bivariate VAR(2) course of utilizing the next specification,

[

begin{bmatrix} y_{1,t} y_{2,t}

end{bmatrix}

= mub + {bf A}_1 begin{bmatrix} y_{1,t-1} y_{2,t-1}

end{bmatrix} + {bf A}_2 begin{bmatrix} y_{1,t-2} y_{2,t-2}

end{bmatrix} + epsb_t

]

the place (y_{1,t}) and (y_{2,t}) are the noticed sequence at time (t), (mub) is a (2 instances 1) vector of intercepts, ({bf A}_1) and ({bf A}_2) are (2times 2) parameter matrices, and (epsb_t) is a (2times 1) vector of improvements that’s uncorrelated over time. I assume a (N({bf 0},Sigmab)) distribution for the improvements (epsb_t), the place (Sigmab) is a (2times 2) covariance matrix.

I set my pattern dimension to 1,100 and generate variables to carry the noticed sequence and improvements.

. clear all

. set seed 2016

. native T = 1100

. set obs `T'

variety of observations (_N) was 0, now 1,100

. gen time = _n

. tsset time

time variable: time, 1 to 1100

delta: 1 unit

. generate y1 = .

(1,100 lacking values generated)

. generate y2 = .

(1,100 lacking values generated)

. generate eps1 = .

(1,100 lacking values generated)

. generate eps2 = .

(1,100 lacking values generated)

In traces 1–6, I set the seed for the random-number generator, set my pattern dimension to 1,100, and generate a time variable, time. Within the remaining traces, I generate variables y1, y2, eps1, and eps2 to carry the noticed sequence and improvements.

Setting parameter values

I select the parameter values for the VAR(2) mannequin as follows:

[

mub = begin{bmatrix} 0.1 0.4 end{bmatrix}, quad {bf A}_1 =

begin{bmatrix} 0.6 & -0.3 0.4 & 0.2 end{bmatrix}, quad {bf A}_2 =

begin{bmatrix} 0.2 & 0.3 -0.1 & 0.1 end{bmatrix}, quad Sigmab =

begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0.5 0.5 & 1 end{bmatrix}

]

. mata: ------------------------------------------------- mata (kind finish to exit) ----- : mu = (0.1�.4) : A1 = (0.6,-0.3�.4,0.2) : A2 = (0.2,0.3-0.1,0.1) : Sigma = (1,0.5�.5,1) : finish -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In Mata, I create matrices mu, A1, A2, and Sigma to carry the parameter values. Earlier than producing my knowledge, I test whether or not these values correspond to a secure VAR(2) course of. Let

[

{bf F} = begin{bmatrix} {bf A}_1 & {bf A_2} {bf I}_2 & {bf 0}

end{bmatrix}

]

denote a (4times 4) matrix the place ({bf I}_2) is a (2times 2) identification matrix and ({bf 0}) is a (2times 2) matrix of zeros. The VAR(2) course of is secure if the modulus of all eigenvalues of ({bf F}) is lower than 1. The code under computes the eigenvalues.

. mata:

------------------------------------------------- mata (kind finish to exit) -----

: Ok = p = 2 // Ok = variety of variables; p = variety of lags

: F = J(Ok*p,Ok*p,0)

: F[1..2,1..2] = A1

: F[1..2,3..4] = A2

: F[3..4,1..2] = I(Ok)

: X = L = .

: eigensystem(F,X,L)

: L'

1

+----------------------------+

1 | .858715598 |

2 | -.217760515 + .32727213i |

3 | -.217760515 - .32727213i |

4 | .376805431 |

+----------------------------+

: finish

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I assemble the matrix F as outlined above and use the operate eigensystem() to compute its eigenvalues. The matrix X holds the eigenvectors, and L holds the eigenvalues. All eigenvalues in L are lower than 1. The modulus of the second and third advanced eigenvalues is (sqrt{r^2 + c^2} = 0.3931), the place (r) is the actual half and (c) is the advanced half. After checking the steadiness situation, I generate attracts for the VAR(2) mannequin.

Drawing improvements from a multivariate regular

I draw random regular values from (N({bf 0},Sigmab)) and assign them to Stata variables eps1 and eps2.

. mata:

------------------------------------------------- mata (kind finish to exit) -----

: T = strtoreal(st_local("T"))

: u = rnormal(T,2,0,1)*cholesky(Sigma)

: epsmat = .

: st_view(epsmat,.,"eps1 eps2")

: epsmat[1..T,.] = u

: finish

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I assign the pattern dimension, outlined in Stata as a neighborhood macro T, to a Mata numeric variable. This simplifies altering the pattern dimension sooner or later; I solely want to do that as soon as originally. In Mata, I exploit two features: st_local() and strtoreal() to assign the pattern dimension. The primary operate obtains strings from Stata macros, and the second operate converts them into an actual worth.

The second line attracts a (1100 instances 2) matrix of regular errors from a (N({bf 0},Sigmab)) distribution. I exploit the st_view() operate to assign the attracts to the Stata variables eps1 and eps2. This operate creates a matrix that could be a view on the present Stata dataset. I create a null matrix epsmat and use st_view() to switch epsmat based mostly on the values of the Stata variables eps1 and eps2. Lastly, I assign this matrix to carry the attracts saved in u, successfully populating the Stata variables eps1 and eps2 with the random attracts.

Producing the noticed sequence

Following Lütkepohl (2005, 708), I generate the primary two observations in order that their correlation construction is similar as the remainder of the pattern. I assume a bivariate regular distribution with imply equal to the unconditional imply (thetab = ({bf I}_K – {bf A}_1 – {bf A}_2)^{-1}mub). The covariance matrix of the primary two observations of the 2 sequence is

[

text{vec}(Sigmab_y) = ({bf I}_{16} – {bf F} otimes {bf F})^{-1}text{vec}(Sigmab_{epsilon})

]

the place (textual content{vec}()) is an operator that stacks matrix columns, ({bf I}_{16}) is a (16times 16) identification matrix, and (Sigmab_{epsilon} = start{bmatrix} Sigmab & {bf 0} {bf 0} & {bf 0} finish{bmatrix}) is a (4times 4) matrix. The primary two observations are generated as

[

begin{bmatrix} {bf y}_0 {bf y}_{-1} end{bmatrix} = {bf Q} etab + Thetab

]

the place Q is a (4times 4) matrix such that ({bf QQ}’ = Sigmab_y), (etab) is a (4times 1) vector of normal regular improvements and (Thetab = start{bmatrix} thetab thetab finish{bmatrix}) is a (4times 1) vector of means.

The next code generates the primary two observations and assigns the values to the Stata variables y1 and y2.

. mata: ------------------------------------------------- mata (kind finish to exit) ----- : Sigma_e = J(Ok*p,Ok*p,0) : Sigma_e[1..K,1..K] = Sigma : Sigma_y = luinv(I((Ok*p)^2)-F#F)*vec(Sigma_e) : Sigma_y = rowshape(Sigma_y,Ok*p)' : theta = luinv(I(Ok)-A1-A2)*mu : Q = cholesky(Sigma_y)*rnormal(Ok*p,1,0,1) : knowledge = . : st_view(knowledge,.,"y1 y2") : knowledge[1..p,.] = ((Q[3..4],Q[1..2]):+mu)' : finish -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

After producing the primary two observations, I can generate the remainder of the sequence from a VAR(2) course of in Stata as follows:

. forvalues i=3/`T' {

2. qui {

3. exchange y1 = 0.1 + 0.6*l.y1 - 0.3*l.y2 + 0.2*l2.y1 + 0.3*l2.y2 + eps1 in `

> i'

4. exchange y2 = 0.4 + 0.4*l.y1 + 0.2*l.y2 - 0.1*l2.y1 + 0.1*l2.y2 + eps2 in `

> i'

5. }

6. }

. drop in 1/100

(100 observations deleted)

I added the quietly assertion to suppress the output generated after the exchange command. Lastly, I drop the primary 100 observations as burn-in to mitigate the impact of preliminary values.

Estimation

I exploit the var command to suit a VAR(2) mannequin.

. var y1 y2

Vector autoregression

Pattern: 103 - 1100 Variety of obs = 998

Log probability = -2693.949 AIC = 5.418735

FPE = .7733536 HQIC = 5.43742

Det(Sigma_ml) = .7580097 SBIC = 5.467891

Equation Parms RMSE R-sq chi2 P>chi2

----------------------------------------------------------------

y1 5 1.14546 0.5261 1108.039 0.0000

y2 5 .865602 0.4794 919.1433 0.0000

----------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [95% Conf. Interval]

-------------+----------------------------------------------------------------

y1 |

y1 |

L1. | .5510793 .0324494 16.98 0.000 .4874797 .614679

L2. | .2749983 .0367192 7.49 0.000 .20303 .3469667

|

y2 |

L1. | -.3080881 .046611 -6.61 0.000 -.3994439 -.2167323

L2. | .2551285 .0425803 5.99 0.000 .1716727 .3385844

|

_cons | .1285357 .0496933 2.59 0.010 .0311387 .2259327

-------------+----------------------------------------------------------------

y2 |

y1 |

L1. | .3890191 .0245214 15.86 0.000 .340958 .4370801

L2. | -.0190324 .027748 -0.69 0.493 -.0734175 .0353527

|

y2 |

L1. | .1944531 .035223 5.52 0.000 .1254172 .263489

L2. | .0459445 .0321771 1.43 0.153 -.0171215 .1090106

|

_cons | .4603854 .0375523 12.26 0.000 .3867843 .5339865

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

By default, var estimates the parameters of a VAR mannequin with two lags. The parameter estimates are vital and are much like the true values used to generate the bivariate sequence.

Inference: Impulse response features

Impulse response features (IRF) are helpful to research the response of endogenous variables within the VAR mannequin resulting from an exogenous impulse to one of many improvements. For instance, in a bivariate VAR of inflation and rate of interest, IRFs can hint out the response of rates of interest over time resulting from exogenous shocks to the inflation equation.

Let’s take into account the bivariate mannequin that I used earlier. Suppose I need to estimate the impact of a unit shock in (epsb_t) to the endogenous variables in my system. I do that by changing the VAR(2) course of into an MA((infty)) course of

as

[

{bf y}_t = sum_{p=0}^infty Phib_p mub + sum_{p=0}^infty Phib_p epsb_{t-p}

]

the place (Phib_p) is the MA((infty)) coefficient matrices for the pth lag. Following Lütkepohl (2005, 22–23), the MA coefficient matrices are associated to the AR matrices as follows:

start{align*}

Phib_0 &= {bf I}_2

Phib_1 &= {bf A}_1

Phib_2 &= Phib_1 {bf A}_1 + {bf A}_2 = {bf A}_1^2 + {bf A}_2

&vdots

Phib_i &= Phib_{i-1} {bf A}_1 + Phib_{i-2}{bf A}_2

finish{align*}

Extra formally, the longer term (h) responses of the ith variable resulting from a unit shock within the jth equation at time (t) are given by

[

frac{partial y_{i,t+h}}{partial epsilon_{j,t}} = {Phib_h}_{i,j}

]

The responses are the gathering of parts within the ith row and jth column of the MA((infty)) coefficient matrices. For the VAR(2) mannequin, the primary few responses utilizing the estimated AR parameters are as follows:

start{align*}

start{bmatrix} y_{1,0} y_{2,0} finish{bmatrix} &=

Phib_0 = {bf I}_2 =

start{bmatrix} 1 & 0 0 & 1 finish{bmatrix}

start{bmatrix} y_{1,1} y_{2,1} finish{bmatrix} &=

hat{Phib}_1 = hat{{bf A}}_1 =

start{bmatrix} 0.5510 & -0.3081 0.3890 & 0.1945 finish{bmatrix}

start{bmatrix} y_{1,2} y_{2,2} finish{bmatrix} &= hat{Phib}_2 =

hat{{bf A}}_1^2 + hat{{bf A}}_2 =

start{bmatrix} 0.4588 & 0.0254 0.2710 & -0.0361 finish{bmatrix}

finish{align*}

Future responses of ({bf y}_t) for (t>2) is computed utilizing related recursions. The response of the primary variable resulting from an impulse within the first equation is the vector ((1,0.5510,0.4588,dots)). I get hold of the impulse responses utilizing the irf create command as follows:

. irf create firstirf, set(myirf) (file myirf.irf created) (file myirf.irf now energetic) (file myirf.irf up to date)

This command estimates the IRFs and different statistics in firstirf and saves the file as myirf.irf. The set() choice units the filename myirf.irf because the energetic file. I can record the desk of responses of y1 resulting from an impulse in the identical equation by typing

. irf desk irf, impulse(y1) response(y1) noci Outcomes from firstirf +--------------------+ | | (1) | | step | irf | |--------+-----------| |0 | 1 | |1 | .551079 | |2 | .458835 | |3 | .42016 | |4 | .353356 | |5 | .305343 | |6 | .263868 | |7 | .227355 | |8 | .196142 | +--------------------+ (1) irfname = firstirf, impulse = y1, and response = y1

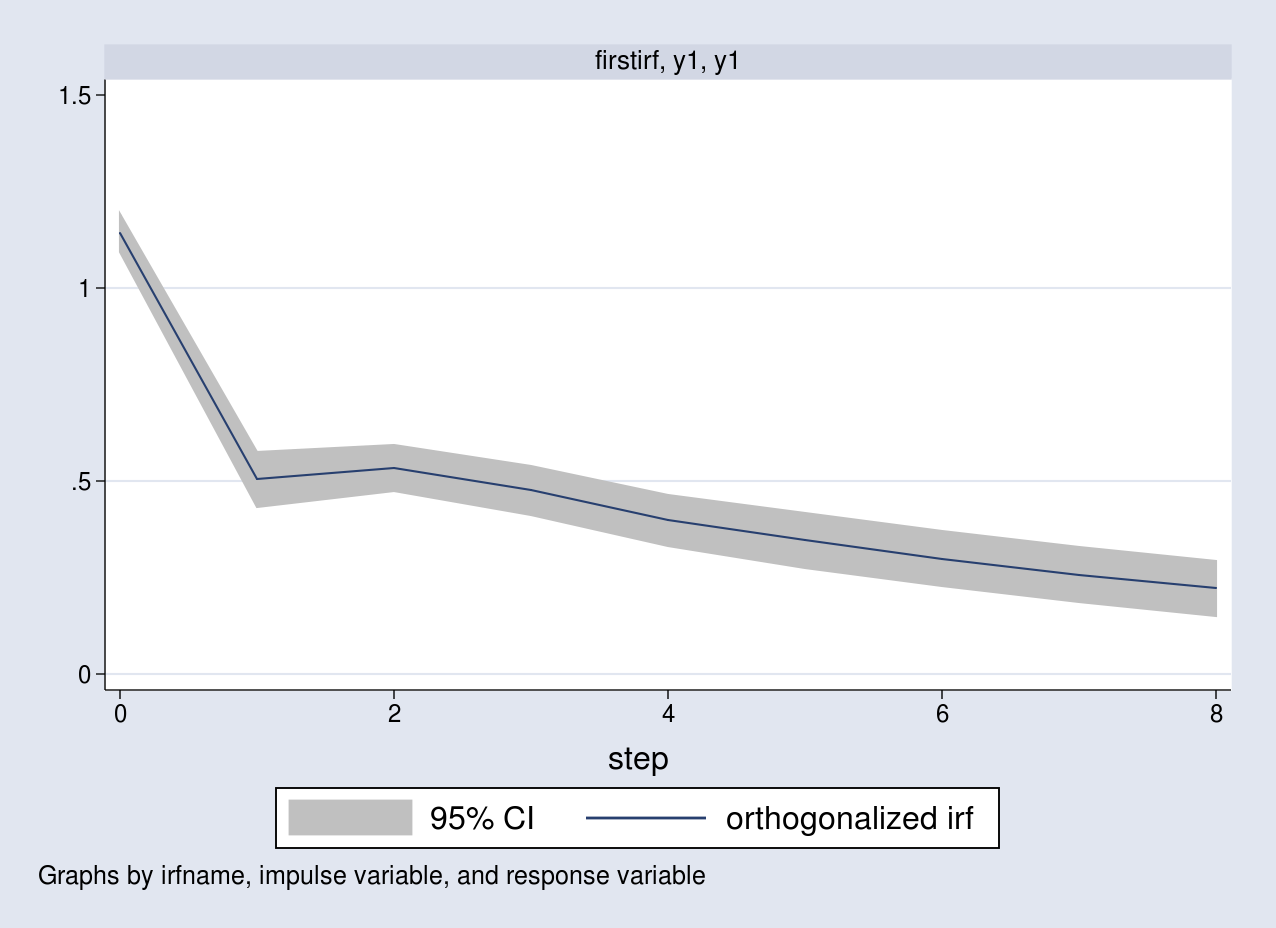

The default horizon is 8, and I specify the noci choice to suppress the arrogance limits. Discover that the primary few responses are much like those I computed earlier. IRFs are higher analyzed utilizing a graph. I can visualize this in a graph together with the 95% confidence bands by typing

. irf graph irf, impulse(y1) response(y1)

A unit impulse to the primary equation will increase y1 by a unit

contemporaneously. The response of y1 slowly declines over time to its long-run degree.

Orthogonalized impulse–response features

Within the earlier part, I confirmed the response of y1 resulting from a unit impulse on the identical equation whereas holding the opposite impulse fixed. The variance–covariance matrix (Sigmab), nonetheless, implies a powerful optimistic correlation between the 2 equations. I record the contents of the estimated variance–covariance matrix by typing

. matrix record e(Sigma)

symmetric e(Sigma)[2,2]

y1 y2

y1 1.3055041

y2 .4639629 .74551376

The estimated covariance of the 2 equations is optimistic. This means that I can not assume the opposite impulse will stay fixed. An impulse to the y2 equation has a contemporaneous impact on y1, and vice versa.

Orthogonalized impulse-response features (OIRF) handle this by decomposing the estimated variance–covariance matrix (hat{Sigmab}) right into a decrease triangular matrix. This sort of decomposition isolates the contemporaneous response of y1 arising solely due to an impulse in the identical equation. Nonetheless, the impulse on the primary equation will nonetheless contemporaneously have an effect on y2. For instance, if y1 is inflation and y2 is rate of interest, this decomposition implies that shock to inflation impacts each inflation and rates of interest. Nevertheless, a shock to the rate of interest equation solely impacts rates of interest.

To estimate the OIRFs, let ({bf P}) denote the Cholesky decomposition of (Sigmab) such that ({bf P} {bf P}’=Sigmab). Let ({bf u}_t) denote a (2times 1) vector such that ({bf P u}_t = epsb_t), which additionally implies ({bf

u}_t = {bf P}^{-1} epsb_t). The errors in ({bf u}_t) are uncorrelated by building as a result of (E({bf u}_t{bf u}_t’) = {bf P}^{-1}E(epsb_t epsb_t’) {bf P’}^{-1}={bf I}_2). This permits us to interpret the OIRFs as a one standard-deviation impulse to ({bf u}_t).

I rewrite the MA((infty)) illustration from earlier when it comes to the ({bf u}_t) vector as

[

{bf y}_t = sum_{p=0}^infty Phib_p mub + sum_{p=0}^infty Phib_p {bf P u}_{t-p}

]

The OIRFs are merely

[

frac{partial y_{i,t+h}}{partial u_{j,t}} = {Phib_h {bf

P}}_{i,j}

]

the product of the MA coefficient matrices and the decrease triangular matrix P.

I get hold of the estimate of (Phat) by typing

. matrix Sigma_hat = e(Sigma)

. matrix P_hat = cholesky(Sigma_hat)

. matrix record P_hat

P_hat[2,2]

y1 y2

y1 1.1425866 0

y2 .40606367 .76198823

Utilizing this matrix, I compute the primary few responses as follows:

start{align*}

start{bmatrix} y_{1,0} y_{2,0} finish{bmatrix} &=

Phib_0 Phat = {bf I}_2 Phat =

start{bmatrix} 1.1426 & 0 0.4061 & 0.7620 finish{bmatrix}

start{bmatrix} y_{1,1} y_{2,1} finish{bmatrix} &=

hat{Phib}_1 Phat = hat{{bf A}}_1 Phat =

start{bmatrix} 0.5046 & -0.2348 0.5234 & 0.1482 finish{bmatrix}

start{bmatrix} y_{1,2} y_{2,2} finish{bmatrix} &= hat{Phib}_2 Phat

= (hat{{bf A}}_1^2 + hat{{bf A}}_2) Phat =

start{bmatrix} 0.5346 & 0.0194 0.2950 & -0.0275 finish{bmatrix}

finish{align*}

I record all of the OIRFs in a desk and plot the response of y1 resulting from an impulse in y1.

. irf desk oirf, noci

Outcomes from firstirf

+--------------------------------------------------------+

| | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| step | oirf | oirf | oirf | oirf |

|--------+-----------+-----------+-----------+-----------|

|0 | 1.14259 | .406064 | 0 | .761988 |

|1 | .504552 | .523448 | -.23476 | .148171 |

|2 | .534588 | .294977 | .019384 | -.027504 |

|3 | .476019 | .279771 | -.0076 | .013468 |

|4 | .398398 | .242961 | -.010024 | -.00197 |

|5 | .346978 | .206023 | -.003571 | -.003519 |

|6 | .299284 | .178623 | -.004143 | -.001973 |

|7 | .257878 | .154023 | -.003555 | -.002089 |

|8 | .222533 | .13278 | -.002958 | -.001801 |

+--------------------------------------------------------+

(1) irfname = firstirf, impulse = y1, and response = y1

(2) irfname = firstirf, impulse = y1, and response = y2

(3) irfname = firstirf, impulse = y2, and response = y1

(4) irfname = firstirf, impulse = y2, and response = y2

irf desk oirf requests the OIRFs. Discover that the estimates within the first three rows are the identical as those computed above.

. irf graph oirf, impulse(y1) response(y1)

The graph corresponds to the response of y1 on account of a one standard-deviation impulse to the identical equation.

Conclusion

On this submit, I confirmed tips on how to simulate knowledge from a secure VAR(2) mannequin. I estimated the parameters of this mannequin utilizing the var command. I confirmed tips on how to estimate IRFs and OIRFs. The latter obtains the responses utilizing the decrease triangular decomposition of the covariance matrix.

Reference

Lütkepohl, H. 2005. New Introduction to A number of Time Sequence Evaluation. New York: Springer.