This can be a collection! It began a couple of articles in the past, after we discovered that, in keeping with the State of CSS 2025 survey, trigonometric capabilities had been the “Most Hated” CSS function.

I’ve been making an attempt to alter that perspective, so I showcased a number of makes use of for trigonometric capabilities in CSS: one for sin() and cos() and one other on tan(). Nevertheless, that’s solely half of what trigonometric capabilities can do. So in the present day, we’ll poke on the inverse world of trigonometric capabilities: asin(), acos(), atan() and atan2().

CSS Trigonometric Capabilities: The “Most Hated” CSS Characteristic

sin()andcos()tan()asin(),acos(),atan()andatan2()(You might be right here!)

Inverse capabilities?

Recapping issues a bit, given an angle, the sin(), cos() and tan() capabilities return a ratio presenting the sine, cosine, and tangent of that angle, respectively. And for those who learn the final two components of the collection, you then already know what every of these portions represents.

What if we wished to go the opposite method round? If we now have a ratio that represents the sine, cosine or tangent of an angle, how can we get the unique angle? That is the place inverse trigonometric capabilities are available in! Every inverse operate asks what the mandatory angle is to get a given worth for a selected trigonometric operate; in different phrases, it undoes the unique trigonometric operate. So…

acos()is the inverse ofcos(),asin()is the inverse ofsin(), andatan()andatan2()are the inverse oftan().

They’re additionally known as “arcus” capabilities and written as arcos(), arcsin() and arctan() in most locations. It’s because, in a circle, every angle corresponds to an arc within the circumference.

The size of this arc is the angle instances the circle’s radius. Since trigonometric capabilities reside in a unit circle, the place the radius is the same as 1, the arc size can be the angle, expressed in radians.

Their mathy definitions are a bit boring, to say the least, however they’re simple:

y = acos(x)such thatx = cos(y)y = asin(x)such thatx = sin(y)y = atan(x)such thatx = tan(y)

acos() and asin()

Utilizing acos() and asin(), we will undo cos(θ) and sin(θ) to get the beginning angle, θ. Nevertheless, if we attempt to graph them, we’ll discover one thing odd:

The capabilities are solely outlined from -1 to 1!

Bear in mind, cos() and sin() can take any angle, however they may at all times return a quantity between -1 and 1. For instance, each cos(90°) and cos(270°) (to not point out others) return 0, so which worth ought to acos(0) return? To reply this, each acos() and asin() have their area (their enter) and vary (their output) restricted:

acos()can solely take numbers between-1and1and return angles between0°and180°.asin()can solely take numbers between-1and1and return angles between-90°and90°.

This limits lots of the conditions the place we will use acos() and asin(), since one thing like asin(1.2) doesn’t work in CSS* — in keeping with the spec, going exterior acos() and asin() area returns NaN — which leads us to our subsequent inverse operate…

atan() and atan2()

Equally, utilizing atan(), we will undo tan(θ) to get θ. However, not like asin() and acos(), if we graph it, we’ll discover an enormous distinction:

This time it’s outlined on the entire quantity line! This is smart since tan() can return any quantity between -Infinity and Infinity, so atan() is outlined in that area.

atan() can take any quantity between -Infinity and Infinity and returns angles -90° and 90°.

This makes atan() extremely helpful to search out angles in every kind of conditions, and much more versatile than acos() and asin(). That’s why we’ll be utilizing it, alongside atan2(), going ahead. Though don’t fear about atan2() for now, we’ll get to it later.

Discovering the proper angle

Within the final article, we labored lots with triangles. Particularly, we used the tan() operate to search out one of many sides of a right-angled triangle from the next relationships:

To make it work, we wanted to know one among its sides and the angle, and by fixing the equation, we might get the opposite aspect. Nevertheless, usually, we do know the lengths of the triangle’s sides and what we are literally on the lookout for is the angle. In that case, the final equation turns into:

Triangles and Conic Gradients

Discovering the angle is useful in a lot of circumstances, like in gradients, as an example. In a linear gradient, for instance, if we would like it to go from nook to nook, we’ll should match the gradient’s angle relying on the factor’s dimensions. In any other case, with a hard and fast angle, the gradient received’t change if the factor will get resized:

.gradient {

background: repeating-linear-gradient(ghostwhite 0px 25px, darkslategray 25px 50px);

}This can be the specified look, however I feel that almost all usually than not, you need it to match the factor’s dimensions.

Utilizing linear-gradient(), we will simply resolve this utilizing to high proper or to backside left values for the angle, which mechanically units the angle so the gradient goes from nook to nook.

.gradient {

background: repeating-linear-gradient(to high proper, ghostwhite 0px 25px, darkslategray 25px 50px);

}Nevertheless, we don’t have that kind of syntax for different gradients, like a conic-gradient(). For instance, the following conic gradient has a hard and fast angle and received’t change upon resizing the factor.

.gradient {

background: conic-gradient(from 45deg, #84a59d 180deg, #f28482 180deg);

}Fortunately, we will repair this utilizing atan()! We are able to have a look at the gradient as a right-angled triangle, the place the width is the adjoining aspect and the peak the alternative aspect:

Then, we will get the angle utilizing this system:

.gradient {

--angle: atan(var(--height-gradient) / var(--width-gradient));

}Since conic-gradient() begins from the highest edge — conic-gradient(from 0deg) — we’ll should shift it by 90deg to make it work.

.gradient {

--rotation: calc(90deg - var(--angle));

background: conic-gradient(from var(--rotation), #84a59d 180deg, #f28482 180deg);

}Chances are you’ll be questioning: can’t we do this with a linear gradient? And the reply is, sure! However this was simply an instance to showcase atan(). Let’s transfer on to extra attention-grabbing stuff that’s distinctive to conic gradients.

I obtained the following instance from Ana Tudor’s submit on “Variable Side Ratio Card With Conic Gradients”:

Fairly cool, proper?. Sadly, Ana’s submit is from 2021, a time when trigonometric capabilities had been specced out however not applied. As she mentions in her article, it wasn’t potential to create these gradients utilizing atan(). Fortunately, we reside sooner or later! Let’s see how easy they turn out to be with trigonometry and CSS.

We’ll use two conic gradients, every of them masking half of the cardboard’s background.

To save lots of time, I’ll gloss over precisely how you can make the unique gradient, so here’s a fast little step-by-step information on how you can make a kind of gradients in a square-shaped factor:

Since we’re working with an ideal sq., we will repair the --angle and --rotation to be 45deg, however for a common use case, every of the conic-gradients would appear like this in CSS:

.gradient {

background:

/* one under */

conic-gradient(

from var(--rotation) at backside left,

#b9eee1 calc(var(--angle) * 1 / 3),

#79d3be calc(var(--angle) * 1 / 3) calc(var(--angle) * 2 / 3),

#39b89a calc(var(--angle) * 2 / 3) calc(var(--angle) * 3 / 3),

clear var(--angle)

),

/* one above */

conic-gradient(

from calc(var(--rotation) + 180deg) at high proper,

#fec9d7 calc(var(--angle) * 1 / 3),

#ff91ad calc(var(--angle) * 1 / 3) calc(var(--angle) * 2 / 3),

#ff5883 calc(var(--angle) * 2 / 3) calc(var(--angle) * 3 / 3),

clear var(--angle)

);

}And we will get these --angle and --rotation variables the identical method we did earlier — utilizing atan(), after all!

.gradient {

--angle: atan(var(--height-gradient) / var(--width-gradient));

--rotation: calc(90deg - var(--angle));

}What about atan2()?

The final instance was all abou atan(), however I informed you we might additionally have a look at the atan2() operate. With atan(), we get the angle after we divide the alternative aspect by the adjoining aspect and move that worth because the argument. On the flip aspect, atan2() takes them as separate arguments:

atan(reverse/adjoining)atan2(reverse, adjoining)

What’s the distinction? To elucidate, let’s backtrack a bit.

We used atan() within the context of triangles, which means that the adjoining and reverse sides had been at all times optimistic. This will look like an apparent factor since lengths are at all times optimistic, however we received’t at all times work with lengths.

Think about we’re in a x-y aircraft and choose a random level on the graph. Simply by its place, we will know its x and y coordinates, which may have each damaging and optimistic coordinates. What if we wished its angle as an alternative? Measuring it, after all, from the optimistic x-axis.

Effectively, keep in mind from the final article on this collection that we will additionally outline tan() because the quotient between sin() and cos():

Additionally recall that after we measure the angle from the optimistic x-axis, then sin() returns the y-coordinate and cos() returns the x-coordinate. So, the final system turns into:

And making use of atan(), we will straight get the angle!

This system has one drawback, although. It ought to work for any level within the x-y aircraft, and since each x and y will be damaging, we will confuse some factors. Since we’re dividing the y-coordinate by the x-coordinate, within the eyes of atan(), the damaging y-coordinate appears the identical because the damaging x-coordinate. And if each coordinates are damaging, it might look the identical as if each had been optimistic.

To compensate for this, we now have atan2(), and because it takes the y-coordinate and x-coordinate as separate arguments, it’s sensible sufficient to return the angle in all places within the aircraft!

Let’s see how we will put it to sensible use.

Following the mouse

Utilizing atan2(), we will make components react to the mouse’s place. Why would we need to do this? Meet my buddy Helpy, Clippy’s uglier brother from Microsoft.

Helpy desires to at all times be wanting on the consumer’s mouse, and fortuitously, we may help him utilizing atan2(). I received’t go into an excessive amount of element about how Helpy is made, simply know that his eyes are two pseudo-elements:

.helpy::earlier than,

.helpy::after {

/* eye styling */

}To assist Helpy, we first have to let CSS know the mouse’s present x-y coordinates. And whereas I could not like utilizing JavaScript right here, it’s wanted so as to move the mouse coordinates to CSS as two customized properties that we’ll name --m-x and --m-y.

const physique = doc.querySelector("physique");

// hear for the mouse pointer

physique.addEventListener("pointermove", (occasion) => {

// set variables for the pointer's present coordinates

let x = occasion.clientX;

let y = occasion.clientY;

// assign these coordinates to CSS customized properties in pixel items

physique.fashion.setProperty("--m-x", `${Math.spherical(x)}px`);

physique.fashion.setProperty("--m-y", `${Math.spherical(y)}px`);

});Helpy is at the moment wanting away from the content material, so we’ll first transfer his eyes so that they align with the optimistic x-axis, i.e., to the fitting.

.helpy::earlier than,

.helpy::after {

rotate: 135deg;

}As soon as there, we will use atan2() to search out the precise angle Helpy has to show so he sees the consumer’s mouse. Since Helpy is positioned on the top-left nook of the web page, and the x and y coordinates are measured from there, it’s time to plug these coordinates into our operate: atan2(var(--m-y), var(--m-x)).

.helpy::earlier than,

.helpy::after {

/* rotate the eyes by it is beginning place, plus the atan2 of the coordinates */

rotate: calc(135deg + atan2(var(--m-y), var(--m-x)));

}We are able to make one final enchancment. You’ll discover that if the mouse goes on the little hole behind Helpy, he’s unable to have a look at the pointer. This occurs as a result of we’re measuring the coordinates precisely from the top-left nook, and Helpy is positioned a bit bit away from that.

To repair this, we will translate the origin of the coordinate system straight on Helpy by subtracting the padding and half its dimension:

Which appears like this in CSS:

.helpy::earlier than,

.helpy::after {

rotate: calc(

135deg +

atan2(

var(--m-y) - var(--spacing) - var(--helpy-size) / 2,

var(--m-x) - var(--spacing) - var(--helpy-size) / 2

)

);

}This can be a considerably minor enchancment, however transferring the coordinate origin might be very important if we need to place Helpy in every other place on the display.

Further: Getting the viewport (and something) in numbers

I can’t end this collection with out mentioning a trick to typecast totally different items into easy numbers utilizing atan2() and tan(). It isn’t straight associated to trigonometry however it’s nonetheless tremendous helpful. It was first described amazingly by Jane Ori in 2023, and goes as follows.

If we need to get the viewport as an integer, then we will…

@property --100vw {

syntax: "<size>;";

initial-value: 0px;

inherits: false;

}

:root {

--100vw: 100vw;

--int-width: calc(10000 * tan(atan2(var(--100vw), 10000px)));

}And now: the --int-width variable holds the viewport width as an integer. This appears like magic, so I actually advocate studying Jane Ori’s submit to know it. I even have an article utilizing it to create animations because the viewport is resized!

What about reciprocals?

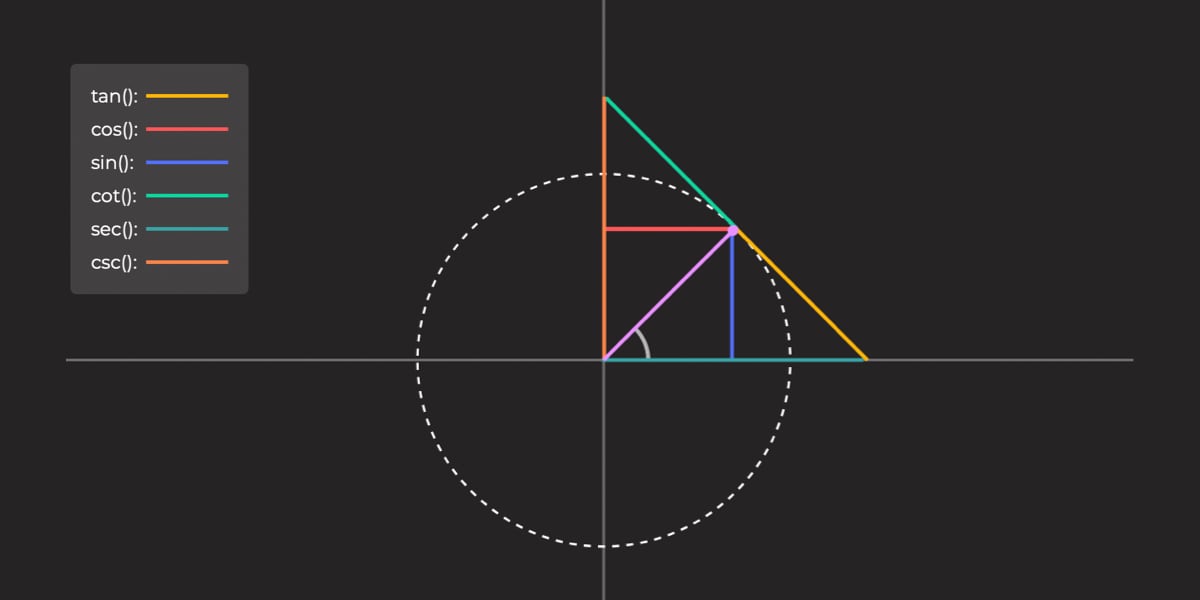

I seen that we’re nonetheless missing the reciprocals for every trigonometric operate. The reciprocals are merely 1 divided by the operate, so there’s a complete of three of them:

- The secant, or

sec(x), is the reciprocal ofcos(x), so it’s1 / cos(x). - The cosecant, or

csc(x), is the reciprocal ofsin(x), so it’s1 / sin(x). - The cotangent, or

cot(x)is the reciprocal oftan(x), so it’s1 / tan(x).

The fantastic thing about sin(), cos() and tan() and their reciprocals is that all of them reside within the unit circle we’ve checked out in different articles on this collection. I made a decision to place every part collectively within the following demo that reveals the entire trigonometric capabilities coated on the identical unit circle:

That’s it!

Welp, that’s it! I hope you realized and had enjoyable with this collection simply as a lot as I loved writing it. And thanks a lot for these of you who’ve shared your individual demos. I’ll be rounding them up in my Bluesky web page.

CSS Trigonometric Capabilities: The “Most Hated” CSS Characteristic

sin()andcos()tan()asin(),acos(),atan()andatan2()(You might be right here!)

The “Most Hated” CSS Characteristic: asin(), acos(), atan() and atan2() initially printed on CSS-Methods, which is a part of the DigitalOcean household. You must get the publication.