In a way, picture segmentation just isn’t that completely different from picture classification. It’s simply that as an alternative of categorizing a picture as an entire, segmentation leads to a label for each single pixel. And as in picture classification, the classes of curiosity depend upon the duty: Foreground versus background, say; several types of tissue; several types of vegetation; et cetera.

The current publish just isn’t the primary on this weblog to deal with that matter; and like all prior ones, it makes use of a U-Internet structure to realize its objective. Central traits (of this publish, not U-Internet) are:

-

It demonstrates easy methods to carry out knowledge augmentation for a picture segmentation process.

-

It makes use of luz,

torch’s high-level interface, to coach the mannequin. -

It JIT-traces the skilled mannequin and saves it for deployment on cellular gadgets. (JIT being the acronym generally used for the

torchjust-in-time compiler.) -

It consists of proof-of-concept code (although not a dialogue) of the saved mannequin being run on Android.

And in the event you suppose that this in itself just isn’t thrilling sufficient – our process right here is to seek out cats and canines. What might be extra useful than a cellular software ensuring you possibly can distinguish your cat from the fluffy couch she’s reposing on?

Practice in R

We begin by getting ready the info.

Pre-processing and knowledge augmentation

As supplied by torchdatasets, the Oxford Pet Dataset comes with three variants of goal knowledge to select from: the general class (cat or canine), the person breed (there are thirty-seven of them), and a pixel-level segmentation with three classes: foreground, boundary, and background. The latter is the default; and it’s precisely the kind of goal we’d like.

A name to oxford_pet_dataset(root = dir) will set off the preliminary obtain:

# want torch > 0.6.1

# might must run remotes::install_github("mlverse/torch", ref = remotes::github_pull("713")) relying on once you learn this

library(torch)

library(torchvision)

library(torchdatasets)

library(luz)

dir <- "~/.torch-datasets/oxford_pet_dataset"

ds <- oxford_pet_dataset(root = dir)Photos (and corresponding masks) come in several sizes. For coaching, nevertheless, we’ll want all of them to be the identical dimension. This may be completed by passing in remodel = and target_transform = arguments. However what about knowledge augmentation (mainly at all times a helpful measure to take)? Think about we make use of random flipping. An enter picture will likely be flipped – or not – in accordance with some chance. But when the picture is flipped, the masks higher had be, as properly! Enter and goal transformations aren’t impartial, on this case.

An answer is to create a wrapper round oxford_pet_dataset() that lets us “hook into” the .getitem() methodology, like so:

pet_dataset <- torch::dataset(

inherit = oxford_pet_dataset,

initialize = operate(..., dimension, normalize = TRUE, augmentation = NULL) {

self$augmentation <- augmentation

input_transform <- operate(x) {

x <- x %>%

transform_to_tensor() %>%

transform_resize(dimension)

# we'll make use of pre-trained MobileNet v2 as a function extractor

# => normalize as a way to match the distribution of photographs it was skilled with

if (isTRUE(normalize)) x <- x %>%

transform_normalize(imply = c(0.485, 0.456, 0.406),

std = c(0.229, 0.224, 0.225))

x

}

target_transform <- operate(x) {

x <- torch_tensor(x, dtype = torch_long())

x <- x[newaxis,..]

# interpolation = 0 makes positive we nonetheless find yourself with integer courses

x <- transform_resize(x, dimension, interpolation = 0)

}

tremendous$initialize(

...,

remodel = input_transform,

target_transform = target_transform

)

},

.getitem = operate(i) {

merchandise <- tremendous$.getitem(i)

if (!is.null(self$augmentation))

self$augmentation(merchandise)

else

checklist(x = merchandise$x, y = merchandise$y[1,..])

}

)All we’ve got to do now’s create a customized operate that lets us determine on what augmentation to use to every input-target pair, after which, manually name the respective transformation features.

Right here, we flip, on common, each second picture, and if we do, we flip the masks as properly. The second transformation – orchestrating random adjustments in brightness, saturation, and distinction – is utilized to the enter picture solely.

We now make use of the wrapper, pet_dataset(), to instantiate the coaching and validation units, and create the respective knowledge loaders.

train_ds <- pet_dataset(root = dir,

break up = "practice",

dimension = c(224, 224),

augmentation = augmentation)

valid_ds <- pet_dataset(root = dir,

break up = "legitimate",

dimension = c(224, 224))

train_dl <- dataloader(train_ds, batch_size = 32, shuffle = TRUE)

valid_dl <- dataloader(valid_ds, batch_size = 32)Mannequin definition

The mannequin implements a basic U-Internet structure, with an encoding stage (the “down” cross), a decoding stage (the “up” cross), and importantly, a “bridge” that passes options preserved from the encoding stage on to corresponding layers within the decoding stage.

Encoder

First, we’ve got the encoder. It makes use of a pre-trained mannequin (MobileNet v2) as its function extractor.

The encoder splits up MobileNet v2’s function extraction blocks into a number of levels, and applies one stage after the opposite. Respective outcomes are saved in a listing.

encoder <- nn_module(

initialize = operate() {

mannequin <- model_mobilenet_v2(pretrained = TRUE)

self$levels <- nn_module_list(checklist(

nn_identity(),

mannequin$options[1:2],

mannequin$options[3:4],

mannequin$options[5:7],

mannequin$options[8:14],

mannequin$options[15:18]

))

for (par in self$parameters) {

par$requires_grad_(FALSE)

}

},

ahead = operate(x) {

options <- checklist()

for (i in 1:size(self$levels)) {

x <- self$levels[[i]](x)

options[[length(features) + 1]] <- x

}

options

}

)Decoder

The decoder is made up of configurable blocks. A block receives two enter tensors: one that’s the results of making use of the earlier decoder block, and one which holds the function map produced within the matching encoder stage. Within the ahead cross, first the previous is upsampled, and handed via a nonlinearity. The intermediate result’s then prepended to the second argument, the channeled-through function map. On the resultant tensor, a convolution is utilized, adopted by one other nonlinearity.

decoder_block <- nn_module(

initialize = operate(in_channels, skip_channels, out_channels) {

self$upsample <- nn_conv_transpose2d(

in_channels = in_channels,

out_channels = out_channels,

kernel_size = 2,

stride = 2

)

self$activation <- nn_relu()

self$conv <- nn_conv2d(

in_channels = out_channels + skip_channels,

out_channels = out_channels,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical"

)

},

ahead = operate(x, skip) {

x <- x %>%

self$upsample() %>%

self$activation()

enter <- torch_cat(checklist(x, skip), dim = 2)

enter %>%

self$conv() %>%

self$activation()

}

)The decoder itself “simply” instantiates and runs via the blocks:

decoder <- nn_module(

initialize = operate(

decoder_channels = c(256, 128, 64, 32, 16),

encoder_channels = c(16, 24, 32, 96, 320)

) {

encoder_channels <- rev(encoder_channels)

skip_channels <- c(encoder_channels[-1], 3)

in_channels <- c(encoder_channels[1], decoder_channels)

depth <- size(encoder_channels)

self$blocks <- nn_module_list()

for (i in seq_len(depth)) {

self$blocks$append(decoder_block(

in_channels = in_channels[i],

skip_channels = skip_channels[i],

out_channels = decoder_channels[i]

))

}

},

ahead = operate(options) {

options <- rev(options)

x <- options[[1]]

for (i in seq_along(self$blocks)) {

x <- self$blocks[[i]](x, options[[i+1]])

}

x

}

)High-level module

Lastly, the top-level module generates the category rating. In our process, there are three pixel courses. The score-producing submodule can then simply be a last convolution, producing three channels:

mannequin <- nn_module(

initialize = operate() {

self$encoder <- encoder()

self$decoder <- decoder()

self$output <- nn_sequential(

nn_conv2d(in_channels = 16,

out_channels = 3,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = "identical")

)

},

ahead = operate(x) {

x %>%

self$encoder() %>%

self$decoder() %>%

self$output()

}

)Mannequin coaching and (visible) analysis

With luz, mannequin coaching is a matter of two verbs, setup() and match(). The training fee has been decided, for this particular case, utilizing luz::lr_finder(); you’ll possible have to alter it when experimenting with completely different types of knowledge augmentation (and completely different knowledge units).

mannequin <- mannequin %>%

setup(optimizer = optim_adam, loss = nn_cross_entropy_loss())

fitted <- mannequin %>%

set_opt_hparams(lr = 1e-3) %>%

match(train_dl, epochs = 10, valid_data = valid_dl)Right here is an excerpt of how coaching efficiency developed in my case:

# Epoch 1/10

# Practice metrics: Loss: 0.504

# Legitimate metrics: Loss: 0.3154

# Epoch 2/10

# Practice metrics: Loss: 0.2845

# Legitimate metrics: Loss: 0.2549

...

...

# Epoch 9/10

# Practice metrics: Loss: 0.1368

# Legitimate metrics: Loss: 0.2332

# Epoch 10/10

# Practice metrics: Loss: 0.1299

# Legitimate metrics: Loss: 0.2511Numbers are simply numbers – how good is the skilled mannequin actually at segmenting pet photographs? To search out out, we generate segmentation masks for the primary eight observations within the validation set, and plot them overlaid on the pictures. A handy method to plot a picture and superimpose a masks is supplied by the raster bundle.

Pixel intensities must be between zero and one, which is why within the dataset wrapper, we’ve got made it so normalization might be switched off. To plot the precise photographs, we simply instantiate a clone of valid_ds that leaves the pixel values unchanged. (The predictions, however, will nonetheless must be obtained from the unique validation set.)

valid_ds_4plot <- pet_dataset(

root = dir,

break up = "legitimate",

dimension = c(224, 224),

normalize = FALSE

)Lastly, the predictions are generated in a loop, and overlaid over the pictures one-by-one:

indices <- 1:8

preds <- predict(fitted, dataloader(dataset_subset(valid_ds, indices)))

png("pet_segmentation.png", width = 1200, top = 600, bg = "black")

par(mfcol = c(2, 4), mar = rep(2, 4))

for (i in indices) {

masks <- as.array(torch_argmax(preds[i,..], 1)$to(machine = "cpu"))

masks <- raster::ratify(raster::raster(masks))

img <- as.array(valid_ds_4plot[i][[1]]$permute(c(2,3,1)))

cond <- img > 0.99999

img[cond] <- 0.99999

img <- raster::brick(img)

# plot picture

raster::plotRGB(img, scale = 1, asp = 1, margins = TRUE)

# overlay masks

plot(masks, alpha = 0.4, legend = FALSE, axes = FALSE, add = TRUE)

}

Now onto working this mannequin “within the wild” (properly, form of).

JIT-trace and run on Android

Tracing the skilled mannequin will convert it to a type that may be loaded in R-less environments – for instance, from Python, C++, or Java.

We entry the torch mannequin underlying the fitted luz object, and hint it – the place tracing means calling it as soon as, on a pattern statement:

m <- fitted$mannequin

x <- coro::accumulate(train_dl, 1)

traced <- jit_trace(m, x[[1]]$x)The traced mannequin may now be saved to be used with Python or C++, like so:

traced %>% jit_save("traced_model.pt")Nonetheless, since we already know we’d prefer to deploy it on Android, we as an alternative make use of the specialised operate jit_save_for_mobile() that, moreover, generates bytecode:

# want torch > 0.6.1

jit_save_for_mobile(traced_model, "model_bytecode.pt")And that’s it for the R aspect!

For working on Android, I made heavy use of PyTorch Cell’s Android instance apps, particularly the picture segmentation one.

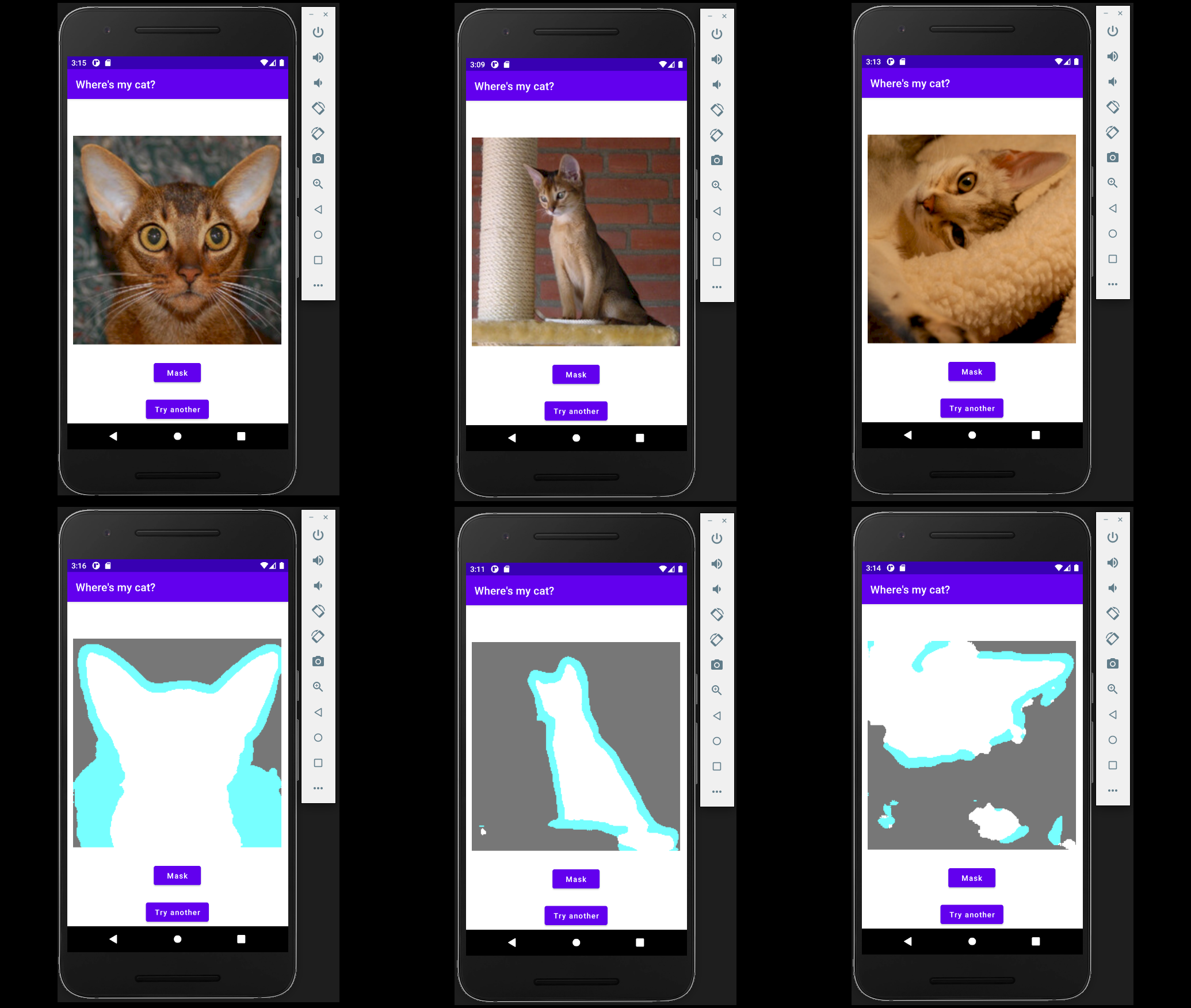

The precise proof-of-concept code for this publish (which was used to generate the under image) could also be discovered right here: https://github.com/skeydan/ImageSegmentation. (Be warned although – it’s my first Android software!).

In fact, we nonetheless must attempt to discover the cat. Right here is the mannequin, run on a tool emulator in Android Studio, on three photographs (from the Oxford Pet Dataset) chosen for, firstly, a variety in issue, and secondly, properly … for cuteness:

Thanks for studying!

Parkhi, Omkar M., Andrea Vedaldi, Andrew Zisserman, and C. V. Jawahar. 2012. “Cats and Canine.” In IEEE Convention on Laptop Imaginative and prescient and Sample Recognition.