Maybe you’ve seen a declare like this in an utilized paper: “the estimated impact for Group A is statistically vital, however the estimated impact for Group B is just not; this therapy helps As however not Bs.”

However this reasoning is flawed.

To see why, think about the next instance from Gelman & Stern.

We have now knowledge from two impartial samples: Group A and Group B.

For Group A our estimated impact is 25 with an ordinary error of 10, yielding an approximate 95% confidence interval of (25 pm 20) or ((5, 45)).

This interval doesn’t embody zero, so the impact for Group A is statistically vital on the 5% stage.

For Group B our estimated impact is 10 with an ordinary error of 10, yielding a confidence interval of (10 pm 20) or ((-10, 30)).

This interval does embody zero, so the impact for Group B is just not statistically vital on the 5% stage.

However there isn’t any statistically vital distinction between the teams: the distinction of means is (25 – 10 = 15) however the usual error for the distinction is (sqrt{10^2 + 10^2} = sqrt{200} approx 14.14).

Thus, the 95% confidence interval for the distinction is (15 pm 28) or ((-13, 43)), which comfortably consists of zero.

To cite the title of the aforementioned paper: The Distinction Between “Important” and “Not Important” is just not Itself Statistically Important.

Meditate on this lesson and repeat it ten instances earlier than going to mattress each night time.

After you’ve performed this, I’ve a puzzle so that you can ponder.

In our instance from above, the intervals for A and B overlap and the distinction is not vital.

Is that this a normal rule?

In different phrases, does overlap within the two intervals indicate no vital distinction between the teams?

Whereas we’re at it, what concerning the reverse case?

If the 2 intervals don’t overlap, does that imply that there is a big distinction between the teams?

Intervals for A, B and their distinction.

Let (bar{A}) be our estimator of the inhabitants imply (mu_A) for Group A, and let (textual content{SE}(bar{A})) be its commonplace error.

Equally, let (bar{B}) be our estimator of the inhabitants imply (mu_B) for Group B, with commonplace error (textual content{SE}(bar{B})).

If the samples we used to assemble (bar{A}) and (bar{B}) are impartial, then (textual content{Cov}(bar{A}, bar{B}) = 0) and

[text{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}) = sqrt{text{SE}(bar{A})^2 + text{SE}(bar{B})^2}]

as within the instance from above. If (bar{A}) and (bar{B}) are roughly usually distributed, say by interesting to the central restrict theorem, then we are able to assemble 95% confidence intervals for (mu_A), (mu_B) as follows

[mu_A colon quad bar{A} pm 2 times text{SE}(bar{A}), quad quad mu_Bcolon quad bar{B} pm 2 times text{SE}(bar{B}).]

Equally, we are able to assemble a confidence interval for the distinction in means (mu_A – mu_B), specifically

[

(bar{A} – bar{B}) pm 2 times text{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}).

]

Extra typically, to assemble an approximate ((1 – alpha) instances 100%) confidence interval, we might substitute the two above with the suitable quantile of an ordinary regular distribution. Beneath I’ll name this quantile (z) for brief.

When is the distinction vital?

The distinction between (mu_A) and (mu_B) is statistically vital on the (alpha instances 100%) stage if the boldness interval for (Delta) doesn’t embody zero, i.e. if (|bar{A} – bar{B}| > z cdot textual content{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B})).

However working with absolute values will rapidly turn into tedious, so with out lack of generality, let’s assume (bar{A} geq bar{B}). If this doesn’t maintain, we are able to at all times relabel the 2 teams so it does maintain. Then the situation for a big distinction turns into

[(bar{A} – bar{B})/z > text{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}).]

When do the intervals overlap?

Once more, with out lack of generality, we are able to assume that (bar{A}geq bar{B}).

Now take into consideration what it could imply for the 2 confidence intervals to overlap.

The middle of the interval for (mu_A) is to the best of the middle of the interval for (mu_B) since (bar{A} geq bar{B}).

So for the 2 intervals to overlap, the decrease confidence restrict of the (mu_A) interval should be to the left of the higher confidence restrict of the (mu_B) interval.

This determine illustrates the logic utilizing (z = 2).

From the determine, we see that the 2 intervals overlap if

[bar{A} – 2 cdot text{SE}(bar{A}) < bar{B} + 2 cdot text{SE}(bar{B})]

Rearranging, and utilizing the generic quantile (z), this turns into

[(bar{A} – bar{B})/z < text{SE}(bar{A}) + text{SE}(bar{B}).]

Formalizing the Query

Can the boldness intervals for A and B overlap regardless of there being a big distinction of means between the 2 teams?

Utilizing the outcomes from above, this query is equal to asking whether or not it’s potential for each of those inequalities to carry on the similar time:

- Overlapping CIs: ((bar{A} – bar{B})/z < textual content{SE}(bar{A}) + textual content{SE}(bar{B}))

- Important Distinction: ((bar{A} – bar{B})/z > textual content{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}))

So the query turns into: can we discover values of (bar{A}), (bar{B}), (textual content{SE}(bar{A})), and (textual content{SE}(bar{B})) such that

[text{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}) < frac{bar{A} – bar{B}}{z} < text{SE}(bar{A}) + text{SE}(bar{B})?]

Let’s discuss triangles!

For only a second, overlook that we’re speaking about statistics and solid your thoughts again to highschool geometry.

There are two information I’d such as you to recall:

1: The Pythagorean Theorem

If (a) and (b) are the lengths of the legs of a proper triangle, then the size (c) of the hypotenuse satisfies (c = sqrt{a^2 + b^2}).

2: The Triangle Inequality

For any triangle with sides (a), (b), and (c), now we have (c leq a + b).

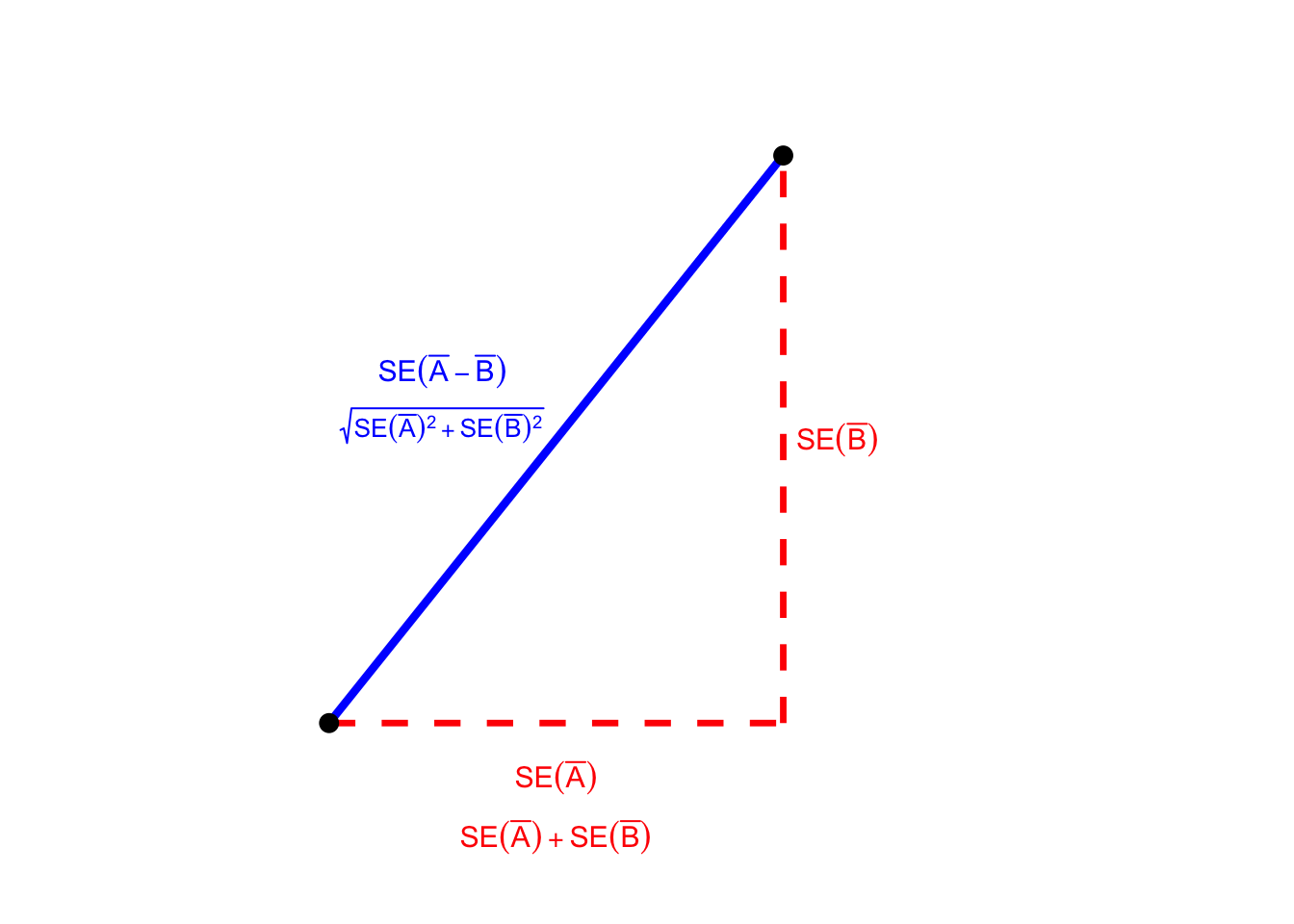

So how do these two information assist us? Take into account a proper triangle whose legs have lengths (textual content{SE}(bar{A})) and (textual content{SE}(bar{B})). By the Pythagorean Theorem, the hypotenuse of this triangle has size

[sqrt{text{SE}(bar{A})^2 + text{SE}(bar{B})^2} = text{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}) ]

and by the triangle inequality, now we have:

[text{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}) < text{SE}(bar{A}) + text{SE}(bar{B}).]

We will learn this inequality from the next determine: travelling alongside the dashed purple path covers a distance of (textual content{SE}(bar{A}) + textual content{SE}(bar{B})), whereas travelling alongside the stable blue path the shorter distance of (textual content{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B})).

The Answer

The query we got down to reply is whether or not we are able to discover values that fulfill the inequality:

[text{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}) < frac{bar{A} – bar{B}}{z} < text{SE}(bar{A}) + text{SE}(bar{B}).]

Because the right-hand facet is at all times strictly bigger than the left-hand facet, the reply is sure.

Let’s attempt it out utilizing a easy instance.

Suppose that (textual content{SE}(bar{A}) = textual content{SE}(bar{B}) = 10) as within the instance from above, and think about a 95% confidence interval in order that (z approx 2).

Then the inequality turns into

[

20 sqrt{2} < bar{A} – bar{B} < 40.

]

Since (20 sqrt{2} approx 28.28) now we have a complete vary of values for (bar{A} – bar{B}) that can do the trick.

For instance, (bar{A}-bar{B} = 30) will do the trick.

So if (textual content{SE}(bar{A}) = textual content{SE}(bar{B}) = 10), (bar{A} = 40) and (bar{B} = 10), the 95% CIs for A and B overlap however there is a big distinction between the 2 teams.

That is the alternative of Gelman & Stern’s instance.

Our inequality from above relies upon solely the distinction between (bar{A}) and (bar{B}), not on the person worth of every pattern imply.

So if we hold the identical commonplace errors as earlier than however set (bar{A} = 15) and (bar{B} = -15), so the distinction of means stays 30, we receive the identical consequence: overlapping intervals with a big distinction between the 2 teams.

Discover something attention-grabbing about this instance?

The interval for A is ((-5,35)) whereas the interval for B is ((-35, 5)).

So each intervals embody zero however there may be nonetheless a big distinction between them!

If all we all know is that two intervals overlap, we are able to’t say something concerning the significance of the distinction.

Now for the straightforward one.

Since

[(bar{A} – bar{B})/z < text{SE}(bar{A}) + text{SE}(bar{B}).]

holds if and provided that the intervals overlap, we merely reverse the inequality to get a situation for intervals that don’t overlap, specifically

[(bar{A} – bar{B})/z > text{SE}(bar{A}) + text{SE}(bar{B}).]

Appending what we realized above from our proper triangle diagram provides

[(bar{A} – bar{B})/z > text{SE}(bar{A}) + text{SE}(bar{B})> text{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B}).]

So if the intervals don’t overlap, then ((bar{A} – bar{B})/z) should be higher than (textual content{SE}(bar{A} – bar{B})), which is exactly the situation for a big distinction between the 2 teams.

In an impartial samples downside the place the 2 particular person confidence intervals overlap, there could or could not be a big distinction between the teams.

Even when the 2 intervals each include zero, there may nonetheless be a big distinction between them.

If the 2 intervals don’t overlap then we are able to conclude that there is a big distinction.

However in the event you solely take one lesson away from this put up it needs to be this one: the distinction between vital and never vital is just not itself vital.

If you wish to perform inference for a distinction, you must assemble the usual error for that distinction.