Overview

Within the frequentist strategy to statistics, estimators are random variables as a result of they’re capabilities of random knowledge. The finite-sample distributions of many of the estimators utilized in utilized work should not identified, as a result of the estimators are difficult nonlinear capabilities of random knowledge. These estimators have large-sample convergence properties that we use to approximate their habits in finite samples.

Two key convergence properties are consistency and asymptotic normality. A constant estimator will get arbitrarily shut in chance to the true worth. The distribution of an asymptotically regular estimator will get arbitrarily near a traditional distribution because the pattern measurement will increase. We use a recentered and rescaled model of this regular distribution to approximate the finite-sample distribution of our estimators.

I illustrate the that means of consistency and asymptotic normality by Monte Carlo simulation (MCS). I exploit a few of the Stata mechanics I mentioned in Monte Carlo simulations utilizing Stata.

Constant estimator

A constant estimator will get arbitrarily shut in chance to the true worth as you enhance the pattern measurement. In different phrases, the chance {that a} constant estimator is exterior a neighborhood of the true worth goes to zero because the pattern measurement will increase. Determine 1 illustrates this convergence for an estimator (theta) at pattern sizes 100, 1,000, and 5,000, when the true worth is 0. Because the pattern measurement will increase, the density is extra tightly distributed across the true worth. Because the pattern measurement turns into infinite, the density collapses to a spike on the true worth.

Determine 1: Densities of an estimator for pattern sizes 100, 1,000, 5,000, and (infty)

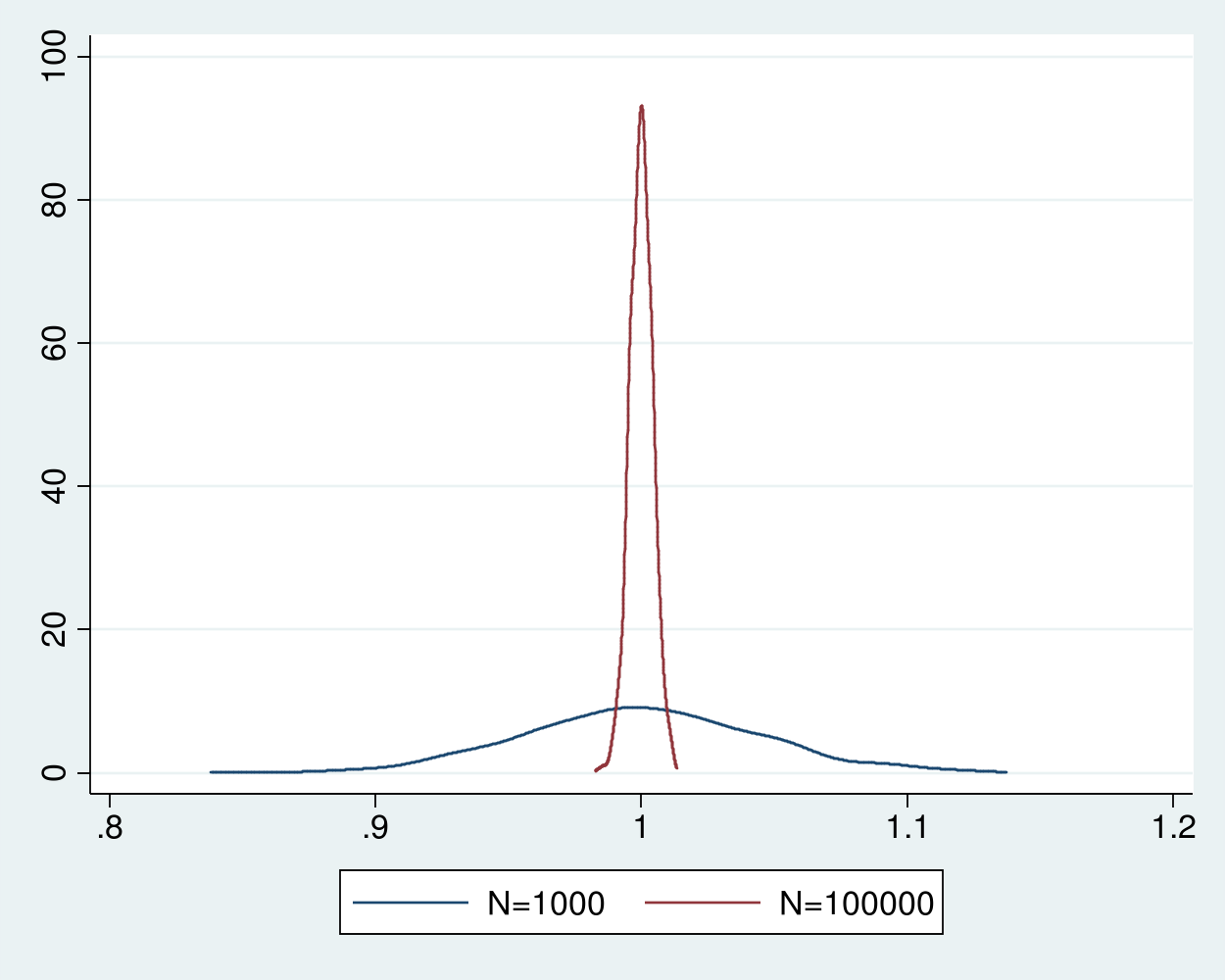

I now illustrate that the pattern common is a constant estimator for the imply of an independently and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variable with a finite imply and a finite variance. On this instance, the info are i.i.d. attracts from a (chi^2) distribution with 1 diploma of freedom. The true worth is 1, as a result of the imply of a (chi^2(1)) is 1.

Code block 1 implements an MCS of the pattern common for the imply from samples of measurement 1,000 of i.i.d. (chi^2(1)) variates.

clear all

set seed 12345

postfile sim m1000 utilizing sim1000, exchange

forvalues i = 1/1000 {

quietly seize drop y

quietly set obs 1000

quietly generate y = rchi2(1)

quietly summarize y

quietly submit sim (r(imply))

}

postclose sim

Line 1 clears Stata, and line 2 units the seed of the random quantity generator. Line 3 makes use of postfile to create a spot in reminiscence named sim, by which I retailer observations on the variable m1000, which would be the new dataset sim1000. Notice that the key phrase utilizing separates the title of the brand new variable from the title of the brand new dataset. The exchange choice specifies that sim1000.dta get replaced, if it already exists.

Strains 5 and 11 use forvalues to repeat the code in traces 6–10 1,000 instances. Every time via the forvalues loop, line 6 drops y, line 7 units the variety of observations to 1,000, line 8 generates a pattern of measurement 1,000 of i.i.d. (chi^2(1)) variates, line 9 estimates the imply of y on this pattern, and line 10 makes use of submit to retailer the estimated imply in what would be the new variable m1000. Line 12 writes every little thing saved in sim to the brand new dataset sim100.dta. See Monte Carlo simulations utilizing Stata for extra particulars about utilizing submit to implement an MCS in Stata.

In instance 1, I run mean1000.do after which summarize the outcomes.

Instance 1: Estimating the imply from a pattern of measurement 1,000

. do mean1000

. clear all

. set seed 12345

. postfile sim m1000 utilizing sim1000, exchange

.

. forvalues i = 1/1000 {

2. quietly seize drop y

3. quietly set obs 1000

4. quietly generate y = rchi2(1)

5. quietly summarize y

6. quietly submit sim (r(imply))

7. }

. postclose sim

.

.

finish of do-file

. use sim1000, clear

. summarize m1000

Variable | Obs Imply Std. Dev. Min Max

-------------+---------------------------------------------------------

m1000 | 1,000 1.00017 .0442332 .8480308 1.127382

The imply of the 1,000 estimates is near 1. The usual deviation of the 1,000 estimates is 0.0442, which measures how tightly the estimator is distributed across the true worth of 1.

Code block 2 incorporates mean100000.do, which implements the analogous MCS with

a pattern measurement of 100,000.

clear all

// no seed, simply preserve drawing

postfile sim m100000 utilizing sim100000, exchange

forvalues i = 1/1000 {

quietly seize drop y

quietly set obs 100000

quietly generate y = rchi2(1)

quietly summarize y

quietly submit sim (r(imply))

}

postclose sim

Instance 2 runs mean100000.do and summarizes the outcomes.

Instance 2: Estimating the imply from a pattern of measurement 100,000

. do mean100000

. clear all

. // no seed, simply preserve drawing

. postfile sim m100000 utilizing sim100000, exchange

.

. forvalues i = 1/1000 {

2. quietly seize drop y

3. quietly set obs 100000

4. quietly generate y = rchi2(1)

5. quietly summarize y

6. quietly submit sim (r(imply))

7. }

. postclose sim

.

.

finish of do-file

. use sim100000, clear

. summarize m100000

Variable | Obs Imply Std. Dev. Min Max

-------------+---------------------------------------------------------

m100000 | 1,000 1.000008 .0043458 .9837129 1.012335

The usual deviation of 0.0043 signifies that the distribution of the estimator with a pattern measurement 100,000 is far more tightly distributed across the true worth of 1 than the estimator with a pattern measurement of 1,000.

Instance 3 merges the 2 datasets of estimates and plots the densities of the estimator for the 2 pattern sizes in determine 2. The distribution of the estimator for the pattern measurement of 100,000 is far tighter round 1 than the estimator for the pattern measurement of 1,000.

Instance 3: Densities of sample-average estimator for 1,000 and 100,000

. merge 1:1 _n utilizing sim1000

Outcome # of obs.

-----------------------------------------

not matched 0

matched 1,000 (_merge==3)

-----------------------------------------

. kdensity m1000, n(500) generate(x_1000 f_1000) kernel(gaussian) nograph

. label variable f_1000 "N=1000"

. kdensity m100000, n(500) generate(x_100000 f_100000) kernel(gaussian) nograph

. label variable f_100000 "N=100000"

. graph twoway (line f_1000 x_1000) (line f_100000 x_100000)

Determine 2: Densities of the sample-average estimator for pattern sizes 1,000 and 100,000

The pattern common is a constant estimator for the imply of an i.i.d. (chi^2(1)) random variable as a result of a weak legislation of huge numbers applies. This theorem specifies that the pattern common converges in chance to the true imply if the info are i.i.d., the imply is finite, and the variance is finite. Different variations of this theorem weaken the i.i.d. assumption or the second assumptions, see Cameron and Trivedi (2005, sec. A.3), Wasserman (2003, sec. 5.3), and Wooldridge (2010, 41–42) for particulars.

Asymptotic normality

So the excellent news is that distribution of a constant estimator is arbitrarily tight across the true worth. The dangerous information is the distribution of the estimator adjustments with the pattern measurement, as illustrated in figures 1 and a couple of.

If I knew the distribution of my estimator for each pattern measurement, I might use it to carry out inference utilizing this finite-sample distribution, also referred to as the precise distribution. However the finite-sample distribution of many of the estimators utilized in utilized analysis is unknown. Luckily, the distributions of a recentered and rescaled model of those estimators will get arbitrarily near a traditional distribution because the pattern measurement will increase. Estimators for which a recentered and rescaled model converges to a traditional distribution are stated to be asymptotically regular. We use this large-sample distribution to approximate the finite-sample distribution of the estimator.

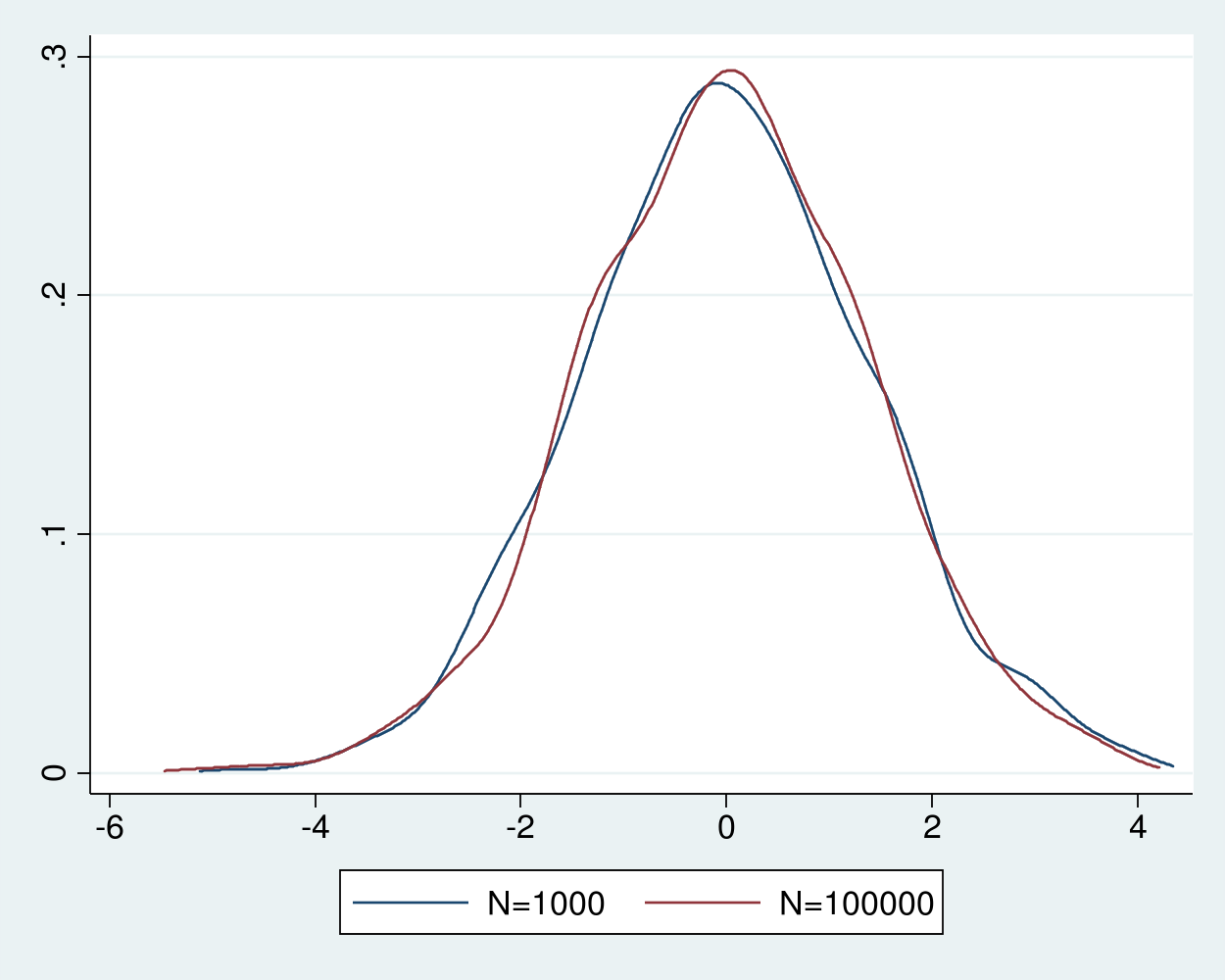

Determine 2 exhibits that the distribution of the pattern common turns into more and more tight across the true worth because the pattern measurement will increase. As a substitute of wanting on the distribution of the estimator (widehat{theta}_N) for pattern measurement (N), let’s take a look at the distribution of (sqrt{N}(widehat{theta}_N – theta_0)), the place (theta_0) is the true worth for which (widehat{theta}_N) is constant.

Instance 4 estimates the densities of the recentered and rescaled estimators, that are proven in determine 3.

Instance 4: Densities of the recentered and rescaled estimator

. generate double m1000n = sqrt(1000)*(m1000 - 1) . generate double m100000n = sqrt(100000)*(m100000 - 1) . kdensity m1000n, n(500) generate(x_1000n f_1000n) kernel(gaussian) nograph . label variable f_1000n "N=1000" . kdensity m100000n, n(500) generate(x_100000n f_100000n) kernel(gaussian) /// > nograph . label variable f_100000n "N=100000" . graph twoway (line f_1000n x_1000n) (line f_100000n x_100000n)

Determine 3: Densities of the recentered and rescaled estimator for pattern sizes 1,000 and 100,000

The densities of the recentered and rescaled estimators in determine 3 are indistinguishable from every and look near a traditional density. The Lindberg–Levy central restrict theorem ensures that the distribution of the recentered and rescaled pattern common of i.i.d. random variables with finite imply (mu) and finite variance (sigma^2) will get arbitrarily nearer to a traditional distribution with imply 0 and variance (sigma^2) because the pattern measurement will increase. In different phrases, the distribution of (sqrt{N}(widehat{theta}_N-mu)) will get arbitrarily near a (N(0,sigma^2)) distribution as (rightarrowinfty), the place (widehat{theta}_N=1/Nsum_{i=1}^N y_i) and (y_i) are realizations of the i.i.d. random variable. This convergence in distribution justifies our use of the distribution (widehat{theta}_Nsim N(mu,frac{sigma^2}{N})) in apply.

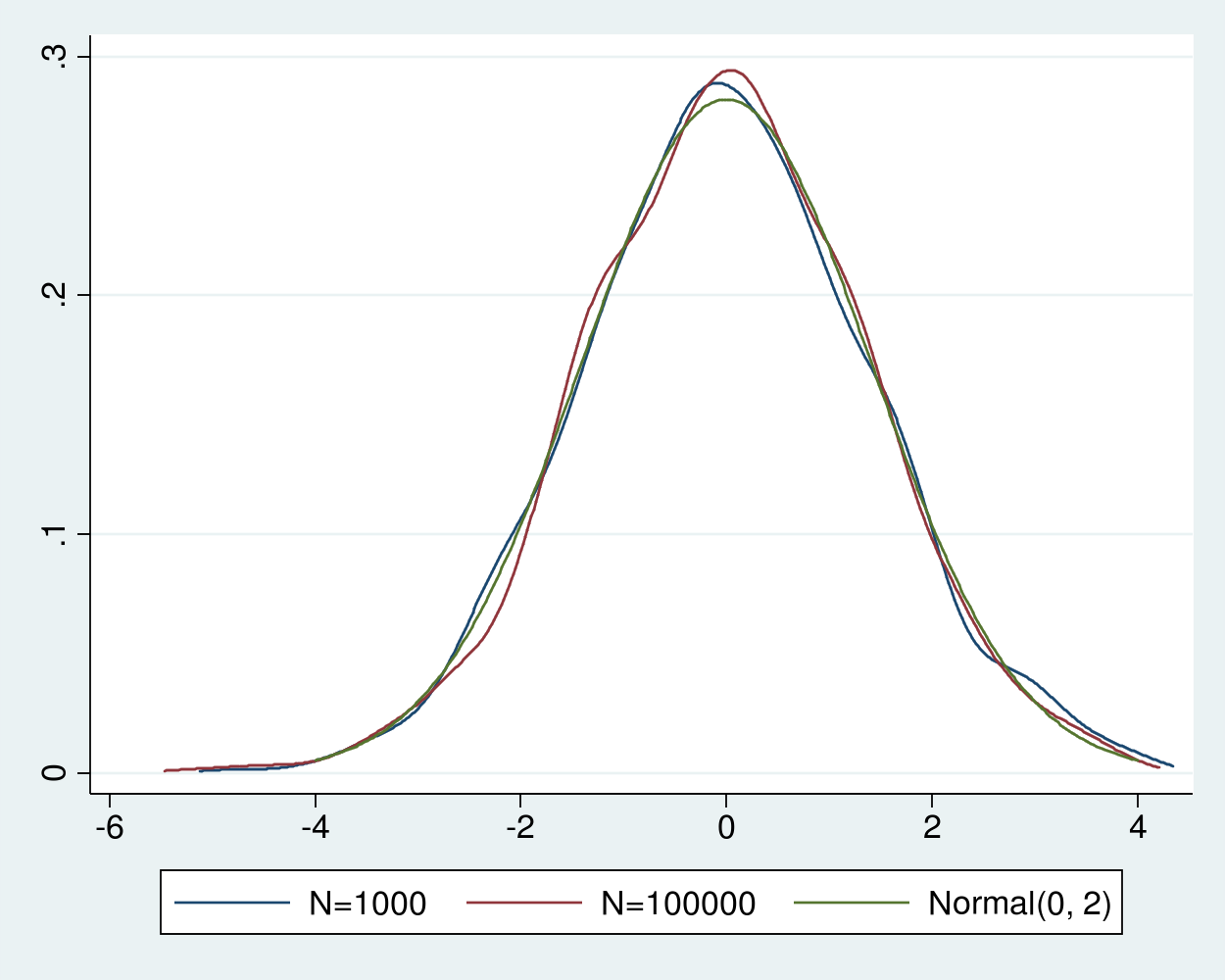

Provided that (sigma^2=2) for the (chi^2(1)) distribution, in instance 5, we add a plot of a traditional density with imply 0 and variance 2 for comparability.

Instance 5: Densities of the recentered and rescaled estimator

. twoway (line f_1000n x_1000n) /// > (line f_100000n x_100000n) /// > (operate normalden(x, sqrt(2)), vary(-4 4)) /// > ,legend( label(3 "Regular(0, 2)") cols(3))

We see that the densities of recentered and rescaled estimators are indistinguishable from the density of a traditional distribution with imply 0 and variance 2, as predicted by the idea.

Determine 4: Densities of the recentered and rescaled estimates and a Regular(0,2)

Different variations of the central restrict theorem weaken the i.i.d. assumption or the second assumptions, see Cameron and Trivedi (2005, sec. A.3), Wasserman (2003, sec. 5.3), and Wooldridge (2010, 41–42) for particulars.

Carried out and undone

I used MCS for instance that the pattern common is constant and asymptotically regular for knowledge drawn from an i.i.d. course of with finite imply and variance.

Many method-of-moments estimators, most chance estimators, and M-estimators are constant and asymptotically regular below assumptions concerning the true data-generating course of and the estimators themselves. See Cameron and Trivedi (2005, sec. 5.3), Newey and McFadden (1994), Wasserman (2003, chap. 9), and Wooldridge (2010, chap. 12) for discussions.

Cameron, A. C., and P. Ok. Trivedi. 2005. Microeconometrics: Strategies and Purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge College Press.

Newey, W. Ok., and D. McFadden. 1994. Massive pattern estimation and speculation testing. In Handbook of Econometrics, ed. R. F. Engle and D. McFadden, vol. 4, 2111–2245. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Wasserman, L. A. 2003. All of Statistics: A Concise Course in Statistical Inference. New York: Springer.

Wooldridge, J. M. 2010. Econometric Evaluation of Cross Part and Panel Information. 2nd ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.